The marsupial mammals (belonging to the clade Metatheria in subclass Theria) are characterized by having a placenta that allows the young to be born very immature; the young are then carried in a pouch. The crown group of the metatherians is known as the Marsupialia (Horowitz et al, 2008), an infraclass within subclass Theria.

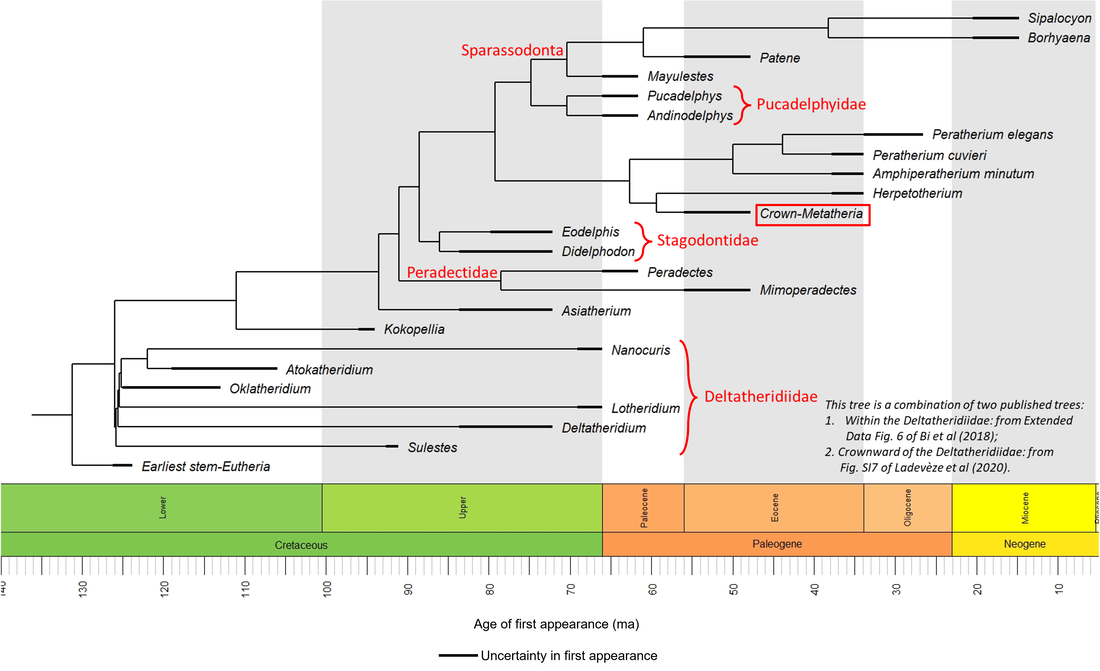

Several phylogenetic trees of the stem-group marsupials have been published in recent years (e.g. Bi et al, 2018; Carneiro et al, 2018; Rangel et al, 2019; Ladevèze et al, 2020; Oliveira et al, 2021). Of these examples, the tree presented by Ladevèze et al (2020), with the addition of some species of the Deltatheridiidae from Bi et al (2018), is the simplest and provides the basis for the time tree shown below:

Several phylogenetic trees of the stem-group marsupials have been published in recent years (e.g. Bi et al, 2018; Carneiro et al, 2018; Rangel et al, 2019; Ladevèze et al, 2020; Oliveira et al, 2021). Of these examples, the tree presented by Ladevèze et al (2020), with the addition of some species of the Deltatheridiidae from Bi et al (2018), is the simplest and provides the basis for the time tree shown below:

Figure 1. Time tree of the stem-Marsupialia

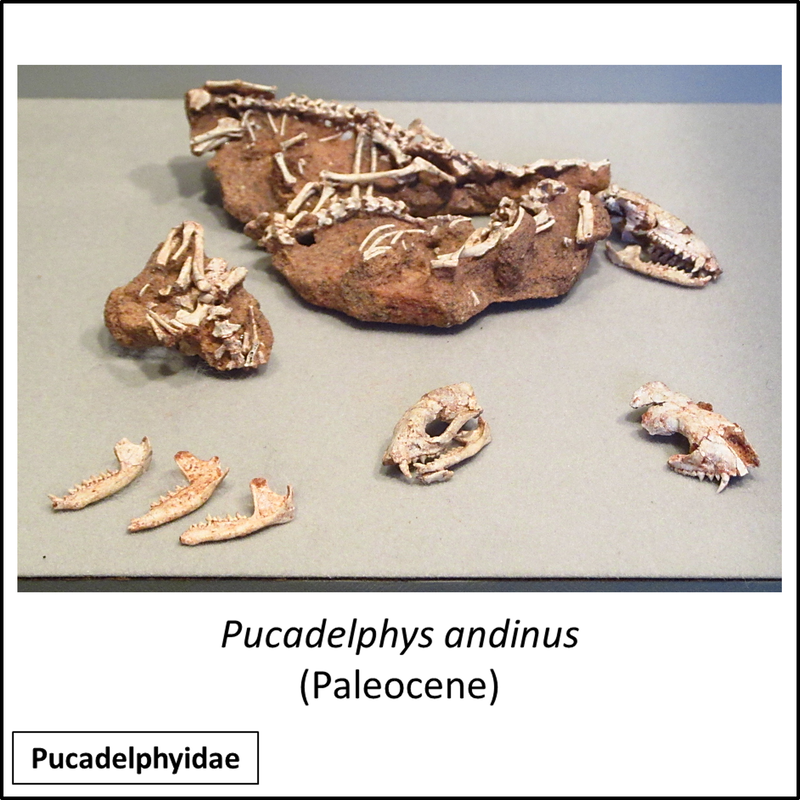

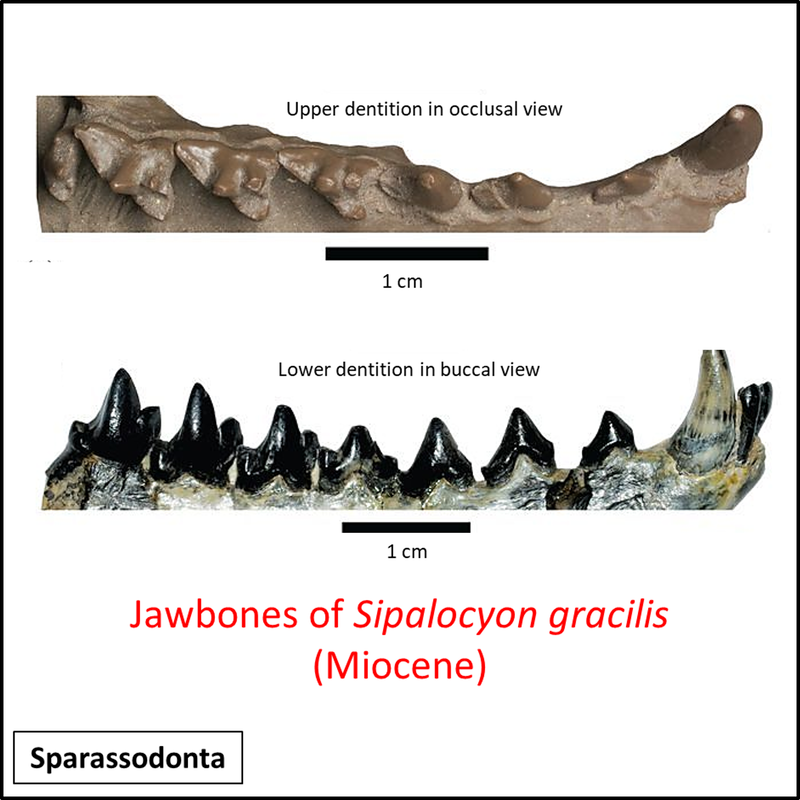

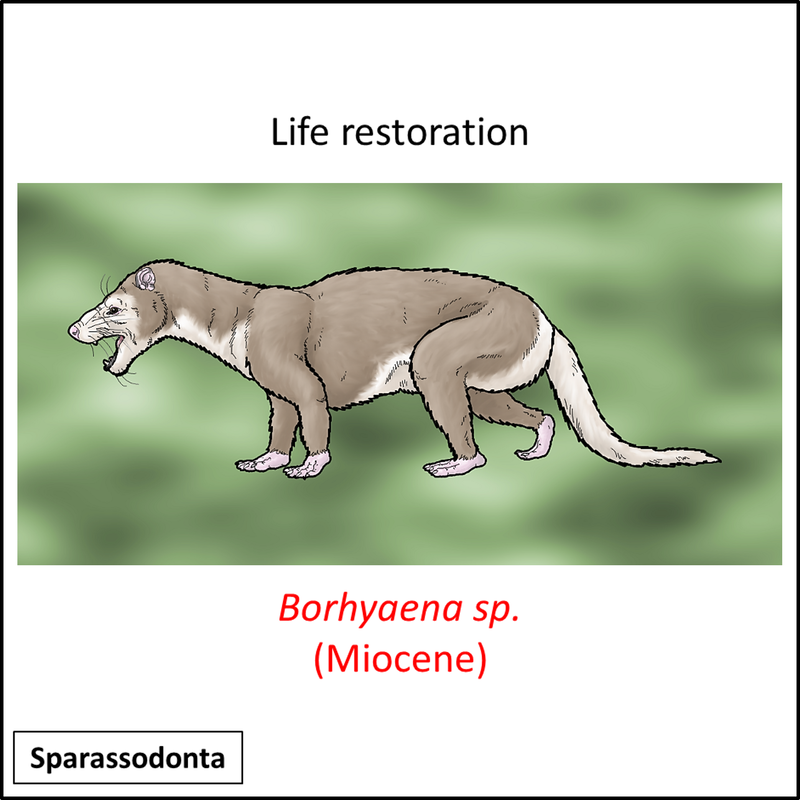

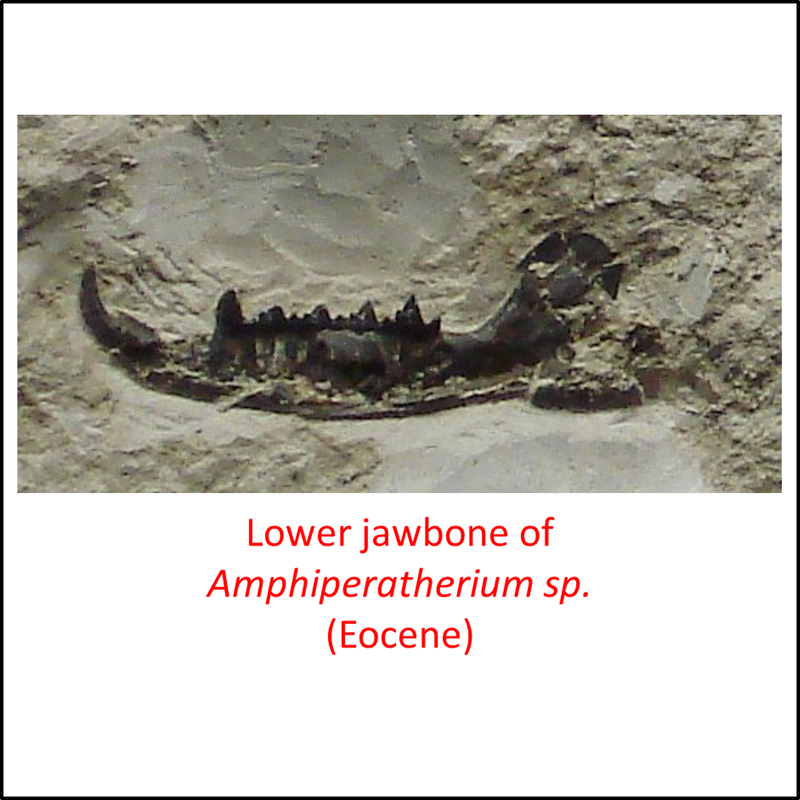

The oldest known member of the marsupial stem group is the genus Oklatheridium, of which several species are known from the Trinity Group of Aptian-Albian age in northern Texas and southern Oklahoma (Davis and Cifelli, 2011) and also from the Cloverly Formation of similar age in Montana and Wyoming (Cifelli and Davis, 2015). The oldest known species is Oklatheridium wiblei, which first appears in the Aptian according to the Paleobiology Database (https://paleobiodb.org/classic). No images of this genus are available in the public domain, but other members of the stem group are illustrated below (for a larger view, click on image):

Names in red indicate that the fossil is younger than the oldest known crown-group fossil.

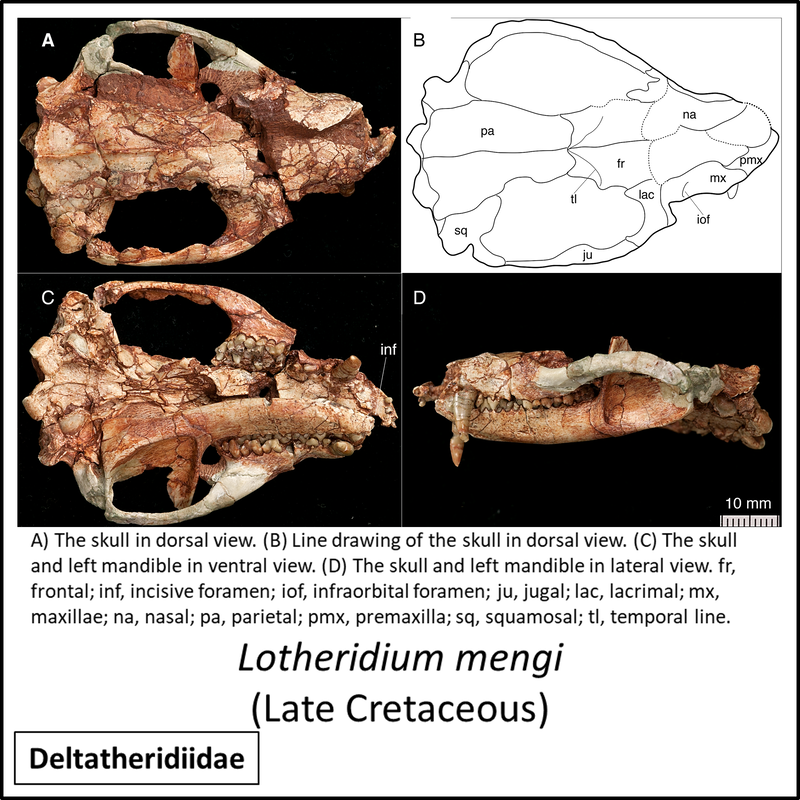

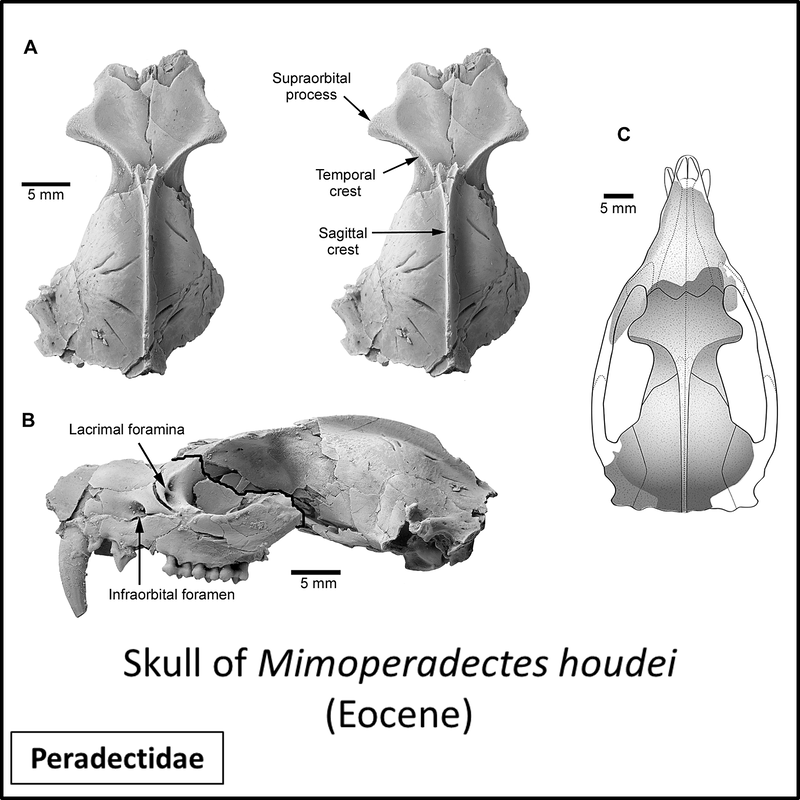

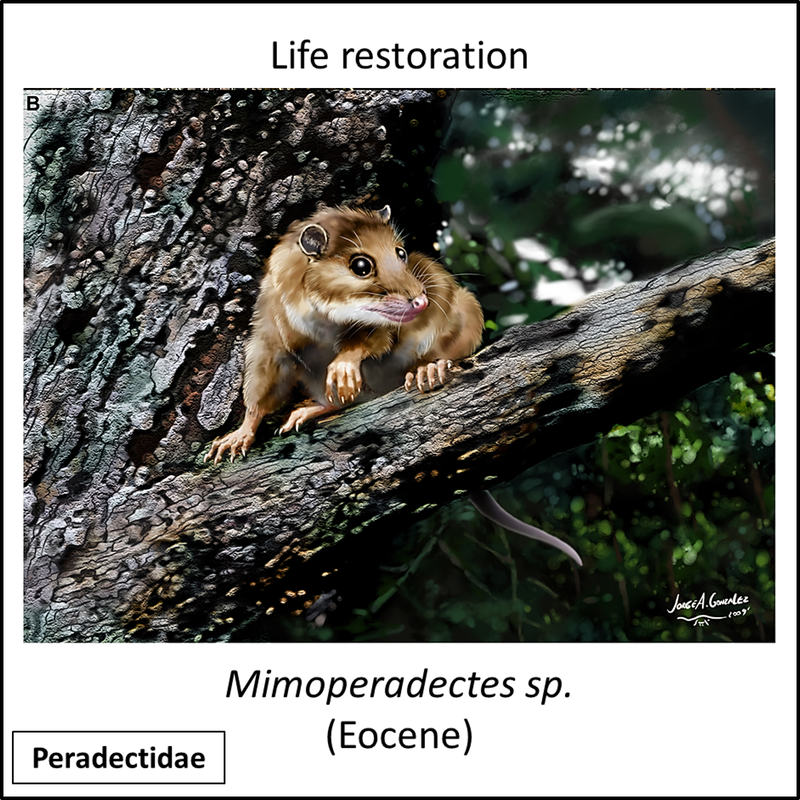

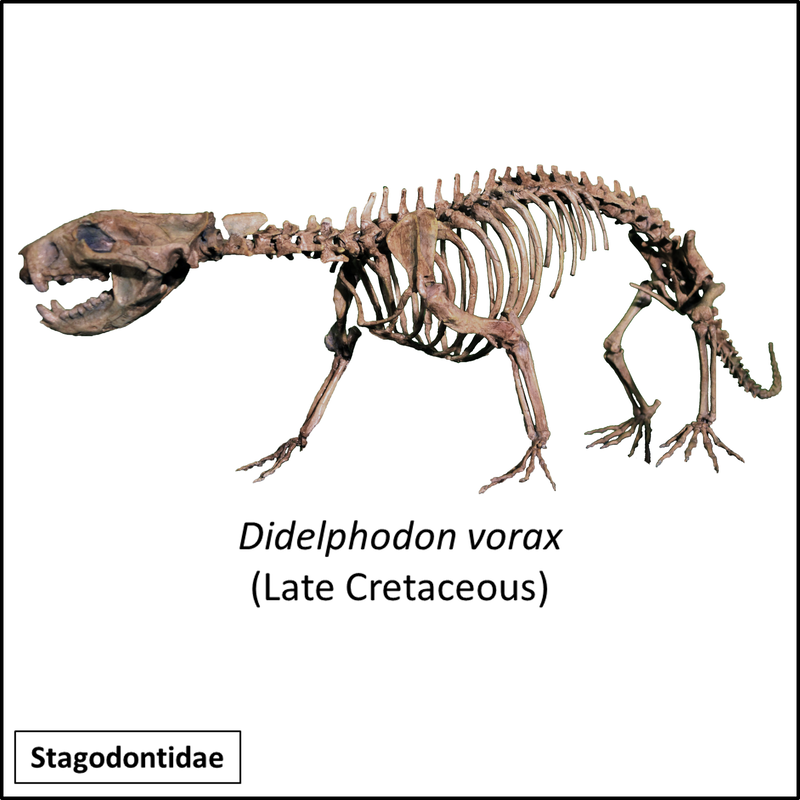

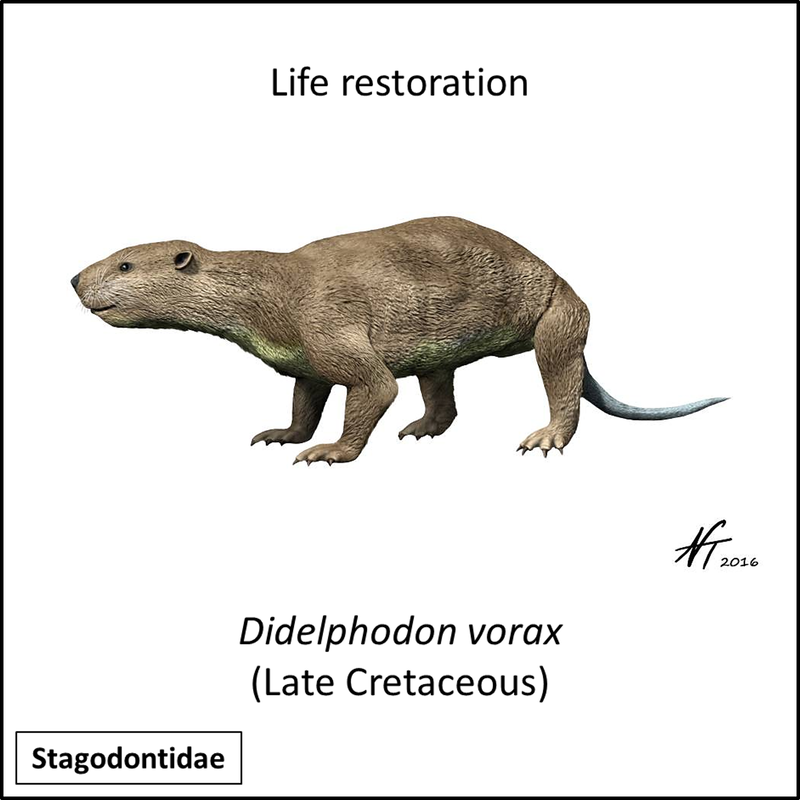

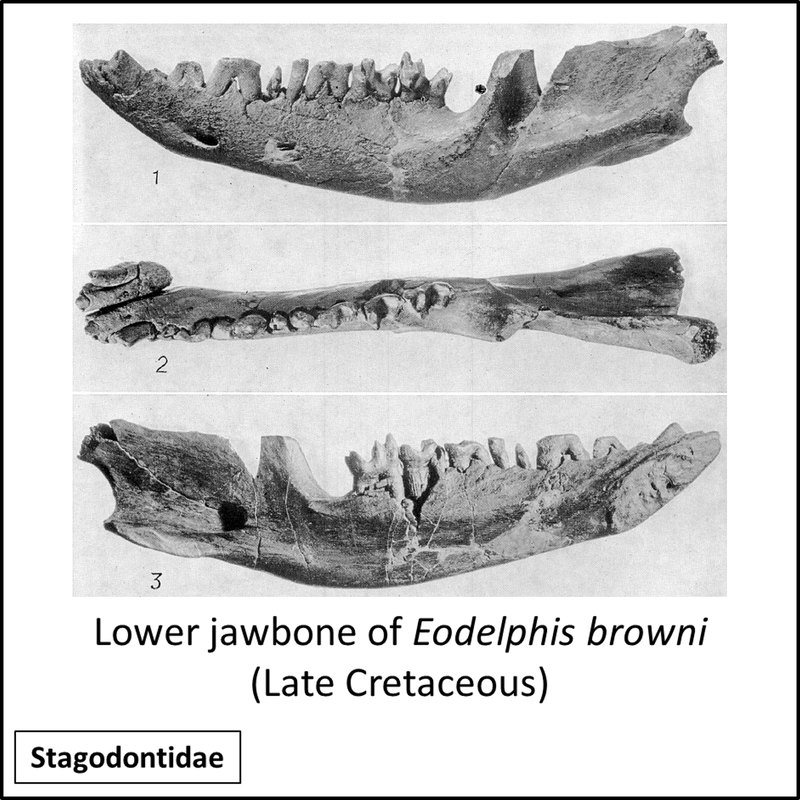

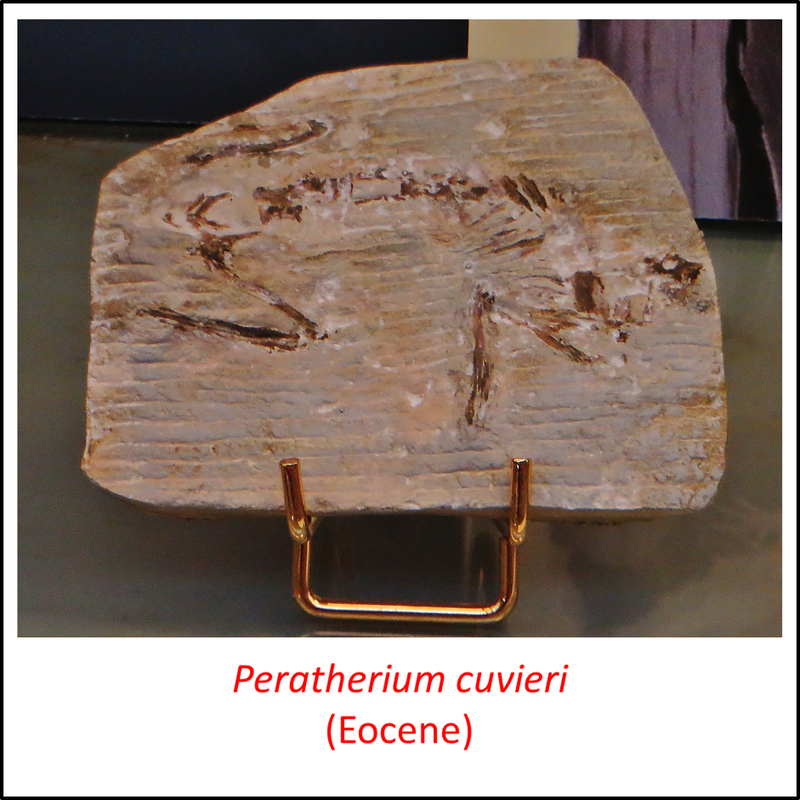

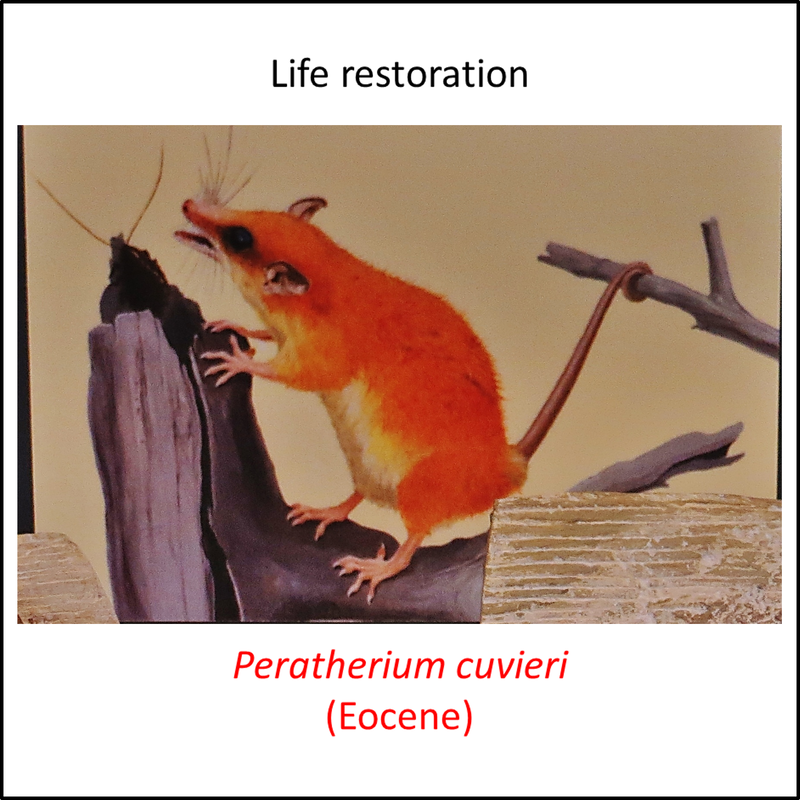

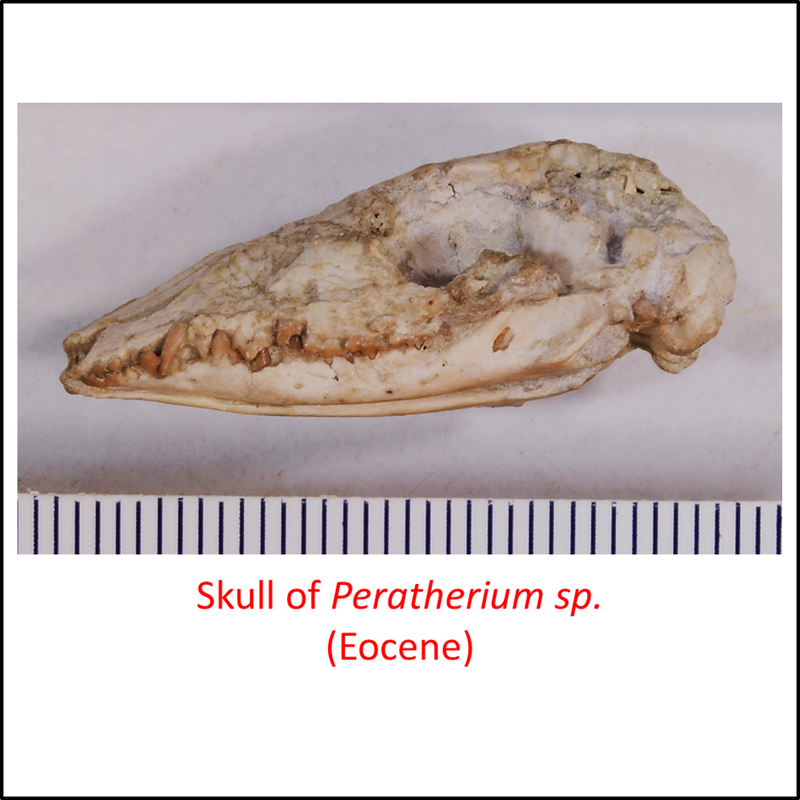

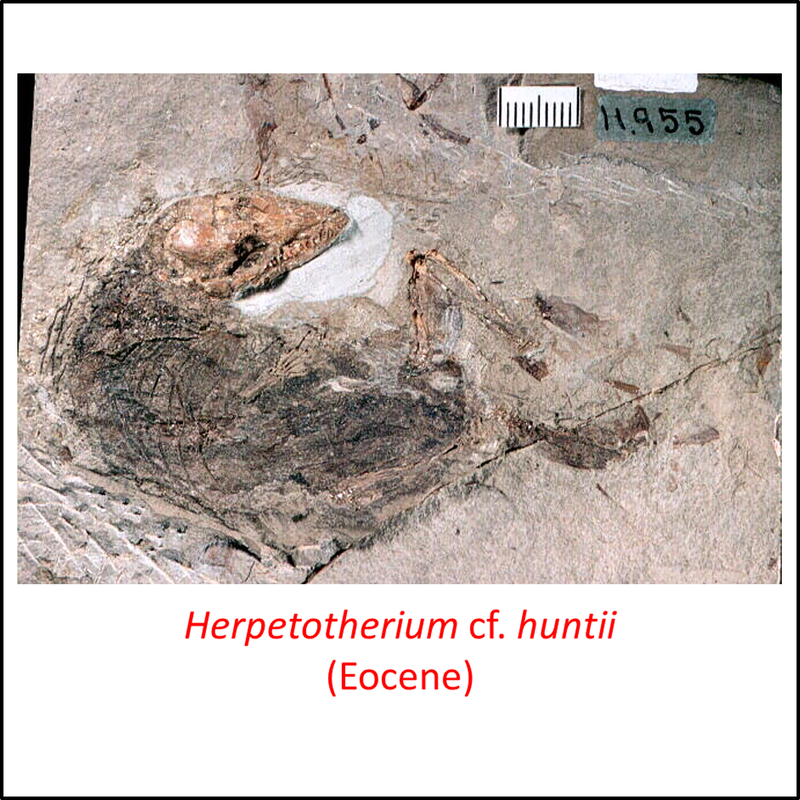

Figure 2. Images of stem-group marsupials

The above images are ordered from most basal to most crownward, but they are of generally limited usefulness and no clear trends in development can be seen. Most of the life restorations suggest a generally rodent-like appearance, but the skeletal details included in the above list of synapomorphies are not representative of rodents.

As in the case of the stem-Theria, some of the stem marsupial fossils have red labels, indicating that they are younger than the metatherian crown group, which appeared in the Early Eocene. They represent descendants of ancestors that would have separated from the stem line during or before the Early Eocene.

The earliest known fossil representative of the metatherian crown group is Djarthia murgonensis, a stem australidelphian from the Early Eocene (Ypresian) "Tingamarra Local Fauna" of Murgon, southeastern Queensland (Godthelp et al, 1999; Benton et al, 2015). Unfortunately, the only images of this fossil available in the public domain show small bones of the skull, which are not very useful for our purpose here.

In contrast to several other taxa (e.g. Theria, Mammalia and Amniota), too few fossils of the crown-Marsupialia are available to adequately illustrate the transition from the marsupial stem group to the crown group.

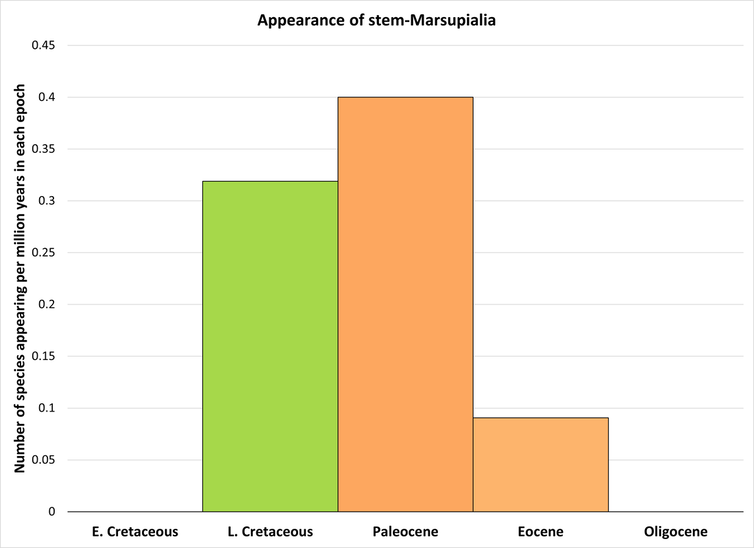

Taking into account the ghost lineage on the marsupial stem line (see Figure 1), the stem group of the Marsupialia must have appeared in Early Cretaceous time, which implies a stem-to-crown transition of at least 67 million years. However, the available fossils suggest that the rate of evolutionary change was highest during the Late Cretaceous and Paleocene, as illustrated in the histogram below:

As in the case of the stem-Theria, some of the stem marsupial fossils have red labels, indicating that they are younger than the metatherian crown group, which appeared in the Early Eocene. They represent descendants of ancestors that would have separated from the stem line during or before the Early Eocene.

The earliest known fossil representative of the metatherian crown group is Djarthia murgonensis, a stem australidelphian from the Early Eocene (Ypresian) "Tingamarra Local Fauna" of Murgon, southeastern Queensland (Godthelp et al, 1999; Benton et al, 2015). Unfortunately, the only images of this fossil available in the public domain show small bones of the skull, which are not very useful for our purpose here.

In contrast to several other taxa (e.g. Theria, Mammalia and Amniota), too few fossils of the crown-Marsupialia are available to adequately illustrate the transition from the marsupial stem group to the crown group.

Taking into account the ghost lineage on the marsupial stem line (see Figure 1), the stem group of the Marsupialia must have appeared in Early Cretaceous time, which implies a stem-to-crown transition of at least 67 million years. However, the available fossils suggest that the rate of evolutionary change was highest during the Late Cretaceous and Paleocene, as illustrated in the histogram below:

Figure 3. Rate of appearance of stem-group marsupials (predating the crown group and including only the genera shown in Figure 1)

References

Benton, M. J. (2015). Vertebrate Palaeontology - Fourth edition. John Wiley & Sons, 468 pages.

Benton, M. J., Donoghue, P. C., Asher, R. J., Friedman, M., Near, T. J., & Vinther, J. (2015). Constraints on the timescale of animal evolutionary history. Palaeontologia Electronica, 18(1), 1-106.

Bi, S., Zheng, X., Wang, X., Cignetti, N. E., Yang, S., & Wible, J. R. (2018). An Early Cretaceous eutherian and the placental–marsupial dichotomy. Nature, 558(7710), 390-395.

Carneiro, L. M., Oliveira, E. V., & Goin, F. J. (2018). Austropediomys marshalli gen. et sp. nov., a new Pediomyoidea (Mammalia, Metatheria) from the Paleogene of Brazil: Paleobiogeographic implications. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia, 21(2), 120-131.

Cifelli, R. L., & Davis, B. M. (2015). Tribosphenic mammals from the Lower Cretaceous Cloverly Formation of Montana and Wyoming. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 35(3), e920848.

Davis, B. M., & Cifelli, R. L. (2011). Reappraisal of the tribosphenidan mammals from the Trinity Group (Aptian—Albian) of Texas and Oklahoma. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 56(3), 441-462.

Horovitz, I., Ladevèze, S., Argot, C., Macrini, T. E., Martin, T., Hooker, J. J., ... & Sánchez-Villagra, M. R. (2008). The anatomy of Herpetotherium cf fugax Cope, 1873, a metatherian from the Oligocene of North America. Palaeontographica Abteilung A, 109-141.

Godthelp, H., Wroe, S., & Archer, M. (1999). A new marsupial from the early Eocene Tingamarra Local Fauna of Murgon, southeastern Queensland: a prototypical Australian marsupial? Journal of Mammalian Evolution, 6(3), 289-313.

Ladevèze, S., Selva, C., & de Muizon, C. (2020). What are “opossum-like” fossils? The phylogeny of herpetotheriid and peradectid metatherians, based on new features from the petrosal anatomy. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 18(17), 1463-1479.

Oliveira, E. V., Carneiro, L. M., & Goin, F. J. (2021). A new derorhynchid (Mammalia, Metatheria) from the early Eocene Itaboraí fauna of Brazil with comments on its affinities. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 93.

Rangel, C. C., Carneiro, L. M., Bergqvist, L. P., Oliveira, É. V., Goin, F. J., & Babot, M. J. (2019). Diversity, affinities and adaptations of the basal sparassodont Patene (Mammalia, Metatheria). Ameghiniana, 56(4), 263-289.

Benton, M. J., Donoghue, P. C., Asher, R. J., Friedman, M., Near, T. J., & Vinther, J. (2015). Constraints on the timescale of animal evolutionary history. Palaeontologia Electronica, 18(1), 1-106.

Bi, S., Zheng, X., Wang, X., Cignetti, N. E., Yang, S., & Wible, J. R. (2018). An Early Cretaceous eutherian and the placental–marsupial dichotomy. Nature, 558(7710), 390-395.

Carneiro, L. M., Oliveira, E. V., & Goin, F. J. (2018). Austropediomys marshalli gen. et sp. nov., a new Pediomyoidea (Mammalia, Metatheria) from the Paleogene of Brazil: Paleobiogeographic implications. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia, 21(2), 120-131.

Cifelli, R. L., & Davis, B. M. (2015). Tribosphenic mammals from the Lower Cretaceous Cloverly Formation of Montana and Wyoming. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 35(3), e920848.

Davis, B. M., & Cifelli, R. L. (2011). Reappraisal of the tribosphenidan mammals from the Trinity Group (Aptian—Albian) of Texas and Oklahoma. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 56(3), 441-462.

Horovitz, I., Ladevèze, S., Argot, C., Macrini, T. E., Martin, T., Hooker, J. J., ... & Sánchez-Villagra, M. R. (2008). The anatomy of Herpetotherium cf fugax Cope, 1873, a metatherian from the Oligocene of North America. Palaeontographica Abteilung A, 109-141.

Godthelp, H., Wroe, S., & Archer, M. (1999). A new marsupial from the early Eocene Tingamarra Local Fauna of Murgon, southeastern Queensland: a prototypical Australian marsupial? Journal of Mammalian Evolution, 6(3), 289-313.

Ladevèze, S., Selva, C., & de Muizon, C. (2020). What are “opossum-like” fossils? The phylogeny of herpetotheriid and peradectid metatherians, based on new features from the petrosal anatomy. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 18(17), 1463-1479.

Oliveira, E. V., Carneiro, L. M., & Goin, F. J. (2021). A new derorhynchid (Mammalia, Metatheria) from the early Eocene Itaboraí fauna of Brazil with comments on its affinities. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 93.

Rangel, C. C., Carneiro, L. M., Bergqvist, L. P., Oliveira, É. V., Goin, F. J., & Babot, M. J. (2019). Diversity, affinities and adaptations of the basal sparassodont Patene (Mammalia, Metatheria). Ameghiniana, 56(4), 263-289.

Image credits – stem- Marsupialia

- Header (Virginia Opossum - Didelphis virginiana): Lauren McLaurin, CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Lotheridium mengi): Open Access article Bi, S., Jin, X., Li, S., & Du, T. (2015). A new Cretaceous metatherian mammal from Henan, China. PeerJ, 3, e896.

- Figure 2 (Asiatherium reshetovi): Ghedoghedo, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Peradectes sp.): Ghedoghedo, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Mimoperadectes houdi): Open Access article Horovitz, I., Martin, T., Bloch, J., Ladevèze, S., Kurz, C., & Sánchez-Villagra, M. R. (2009). Cranial anatomy of the earliest marsupials and the origin of opossums. PLoS One, 4(12), e8278.

- Figure 2 (Mimoperadectes sp.): Open Access article Horovitz, I., Martin, T., Bloch, J., Ladevèze, S., Kurz, C., & Sánchez-Villagra, M. R. (2009). Cranial anatomy of the earliest marsupials and the origin of opossums. PLoS One, 4(12), e8278.

- Figure 2 (Didelphodon vorax, fossil): MCDinosaurhunter, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Didelphodon vorax, life restoration): Nobu Tamura, under Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike (CC BY-SA) license

- Figure 2 (Eodelphis browni): Matthew, William Diller, 1871-1930.Brown, Barnum.Wortman, Jacob Lawson., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Pucadelphys andinus): eduardorudas, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Sipalocyon gracilis): Open Access article Croft, D. A., Engelman, R. K., Dolgushina, T., & Wesley, G. (2018). Diversity and disparity of sparassodonts (Metatheria) reveal non-analogue nature of ancient South American mammalian carnivore guilds. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 285(1870), 20172012.

- Figure 2 (Borhyaena tuberata): Ghedoghedo, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Borhyaena sp.): WSnyder, under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License

- Figure 2 (Amphiperatherium sp.): Ghedoghedo, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Peratherium cuvieri, fossil): Ghedo, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Peratherium cuvieri, life restoration): Ghedo, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Peratherium sp.): Smithsonian Institution, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Herpetotherium cf. huntii): National Park Service, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Herpetotherium sp.): Open Access article Horovitz, I., Martin, T., Bloch, J., Ladevèze, S., Kurz, C., & Sánchez-Villagra, M. R. (2009). Cranial anatomy of the earliest marsupials and the origin of opossums. PLoS One, 4(12), e8278.