This page deals with the stem group of the amphibians (Class Amphibia, Superclass Tetrapoda). This clade comprises comprise three orders, the Anura (the frogs and toads), Caudata (the newts and salamanders) and Gymnophiona (the caecilians). The crown group is known as the Lissamphibia.

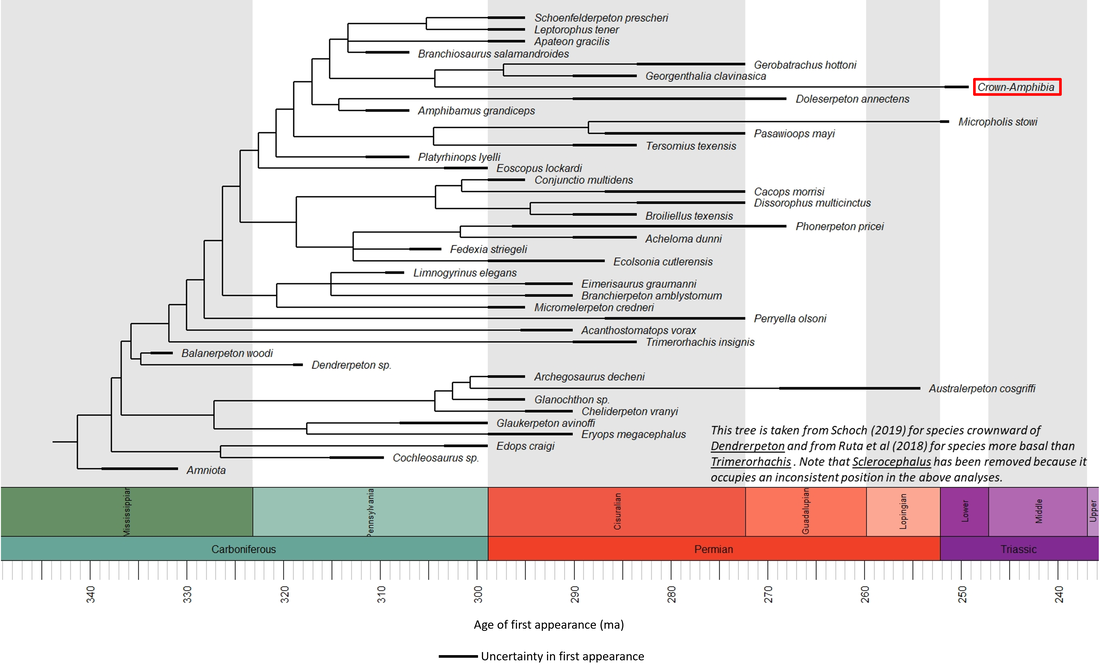

The phylogeny of the amphibian stem group is currently undergoing active research, and there are substantial areas of disagreement between different researchers. One interpretation, based on two fairly recent publications, is shown in the time tree below:

The phylogeny of the amphibian stem group is currently undergoing active research, and there are substantial areas of disagreement between different researchers. One interpretation, based on two fairly recent publications, is shown in the time tree below:

Figure 1. Phylogenetic time tree of the stem-Amphibia

It is important to note that the above phylogenetic tree represents just one of three possible hypotheses for the origin of the amphibians. It is based on the "Temnospondyl Hypothesis" of Ruta and Coates (2007), whereby the modern amphibians evolved from dissorophoid temnospondyls. Alternative ideas are represented by the "Lepospondyl Hypothesis" (Laurin et al, 1997), in which the amphibian crown group developed from the Lepospondyli, a group formerly thought to be monophyletic on the amniote stem (Anderson, 2001) but now considered to be polyphyletic (Pardo et al, 2017), and the "Polyphyletic Hypothesis", in which the modern amphibians are derived from separate groups of Paleozoic tetrapods (Sigurdsen and Green, 2011). Here we follow the Temnospondyl Hypothesis because of the growing consensus that it best represents the origin of the amphibian crown group (Atkins et al, 2019). However, for an alternative view, see Marjanović and Laurin (2019).

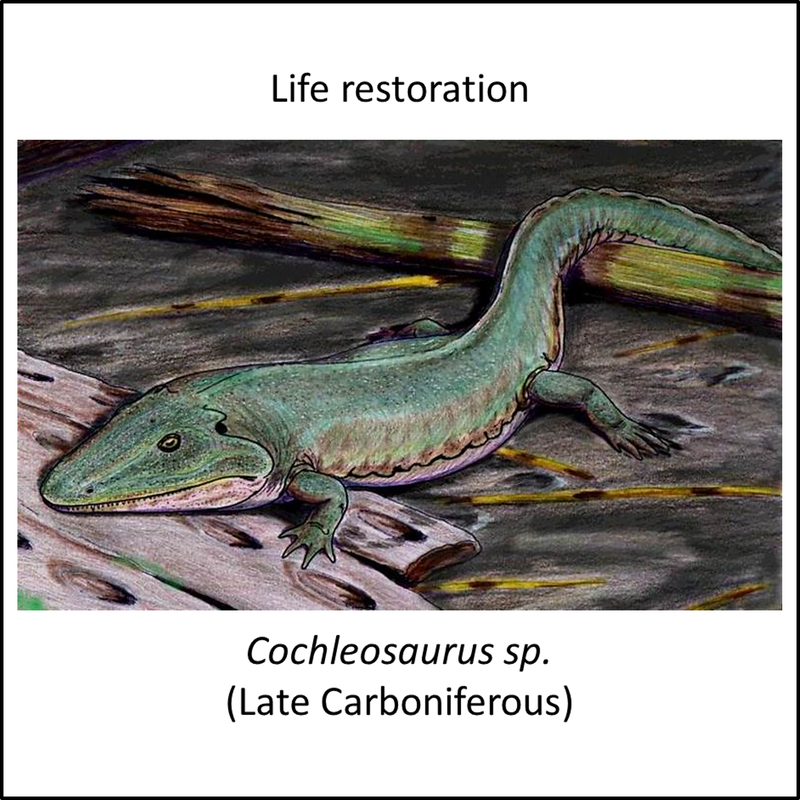

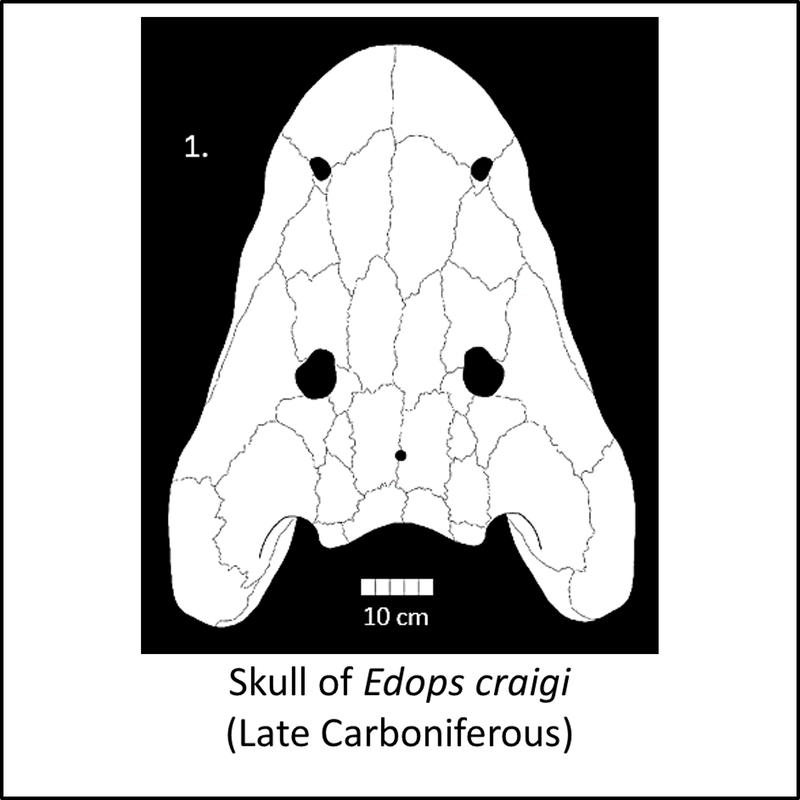

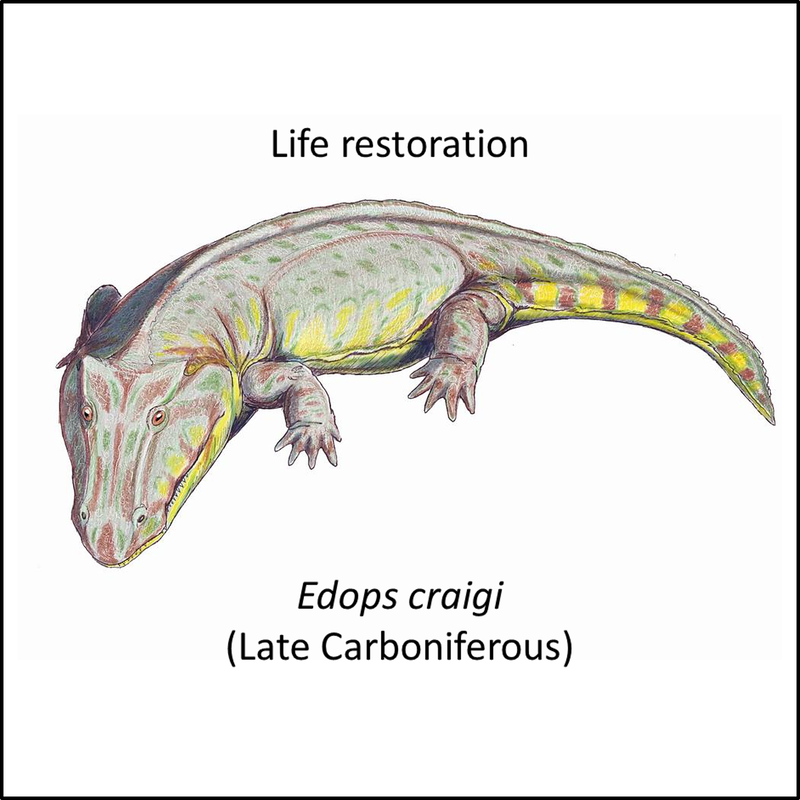

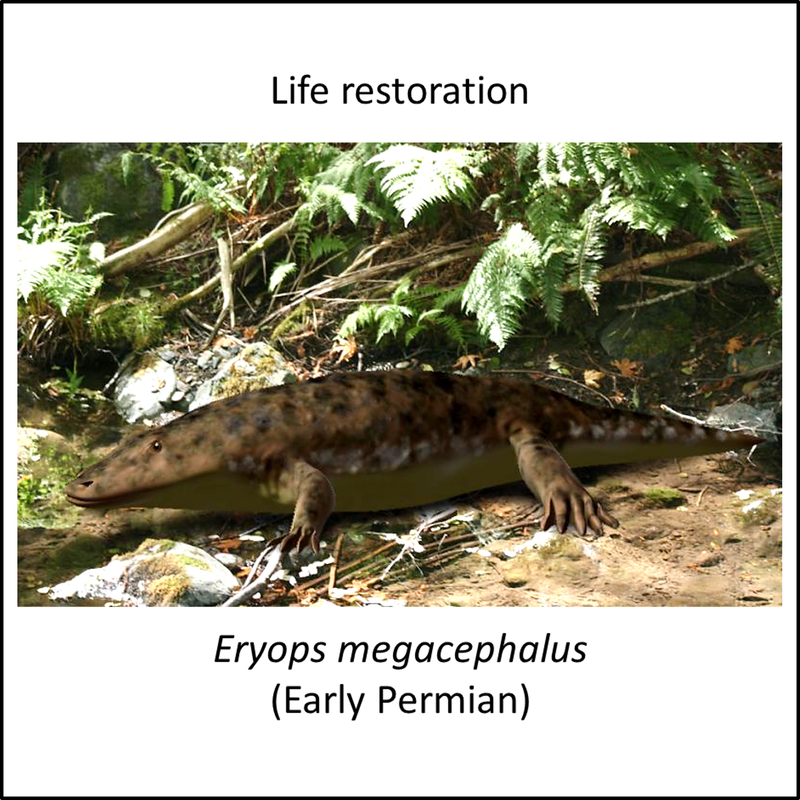

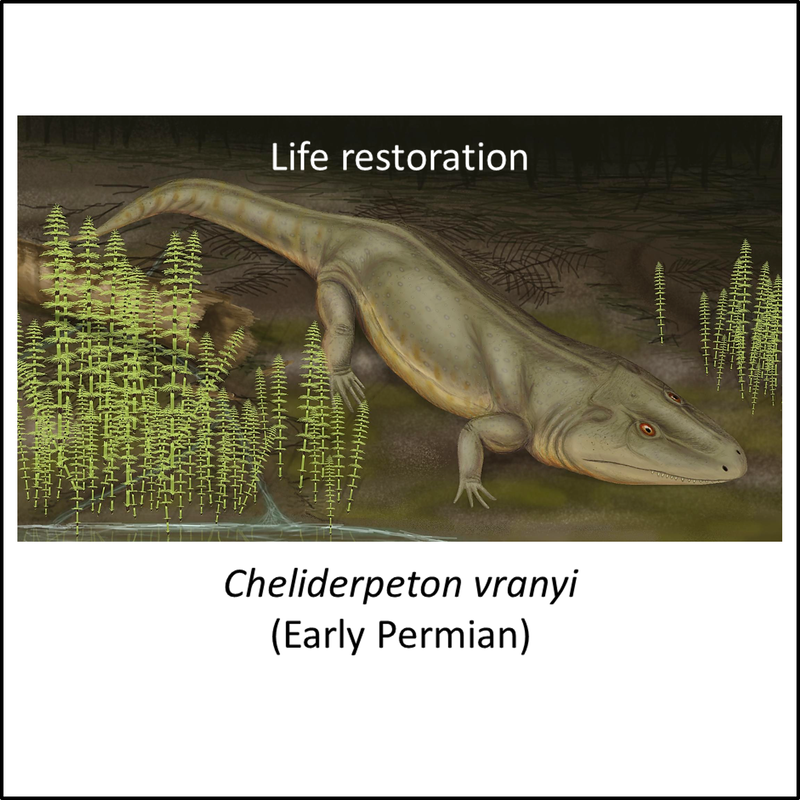

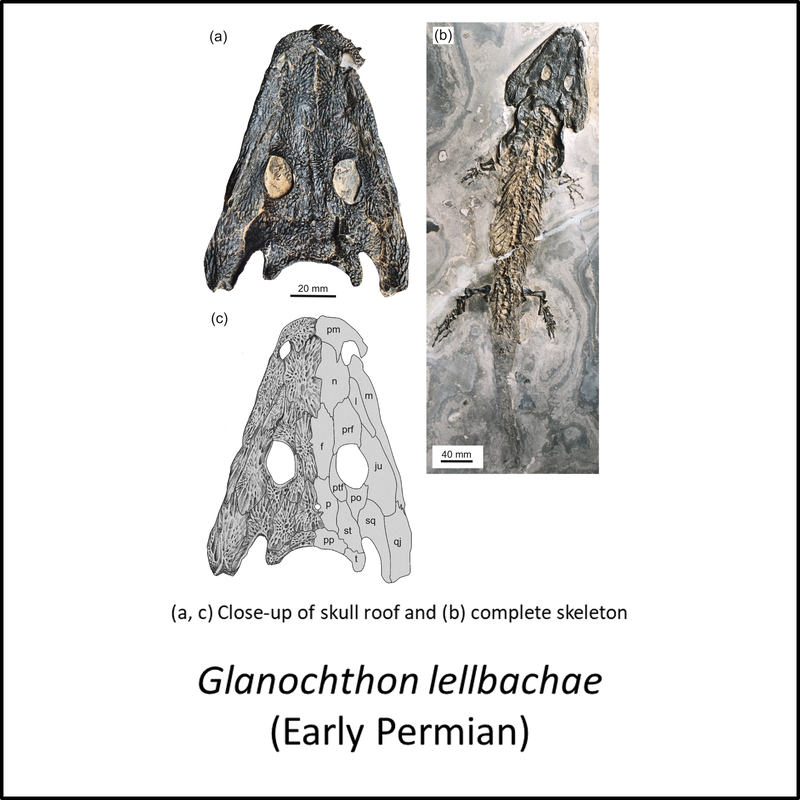

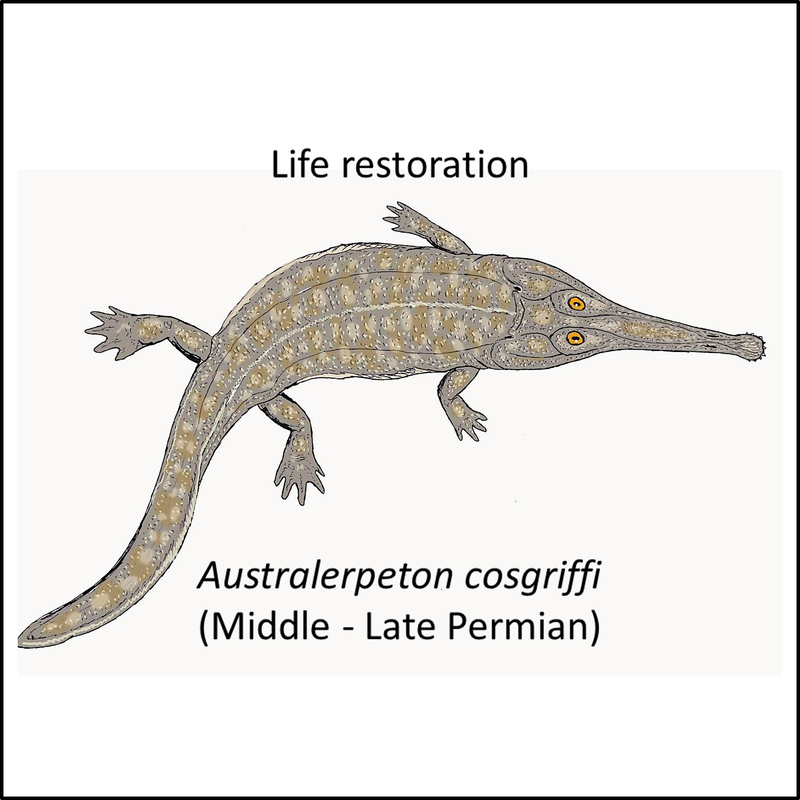

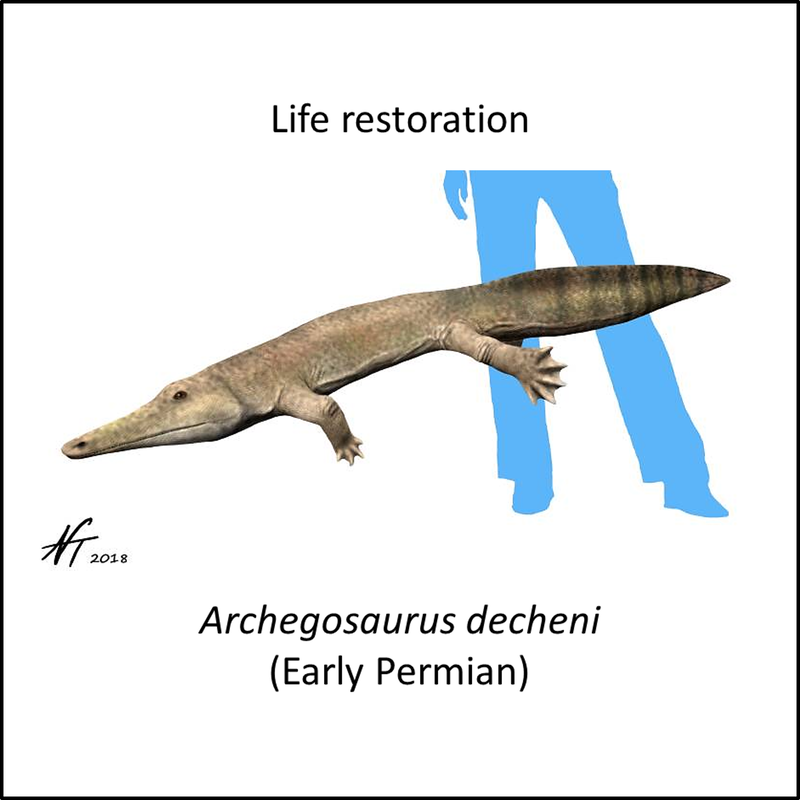

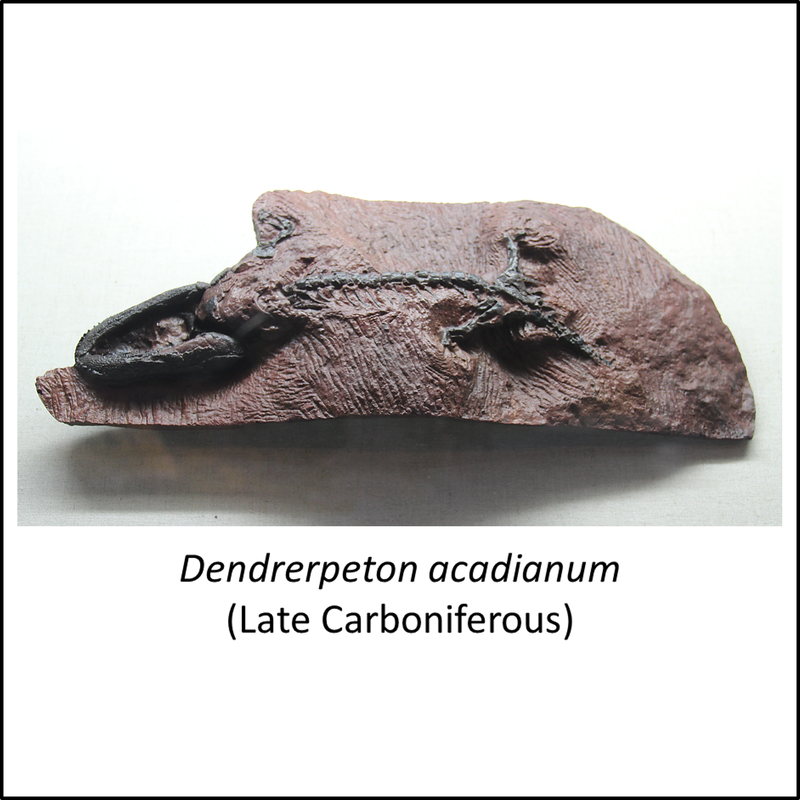

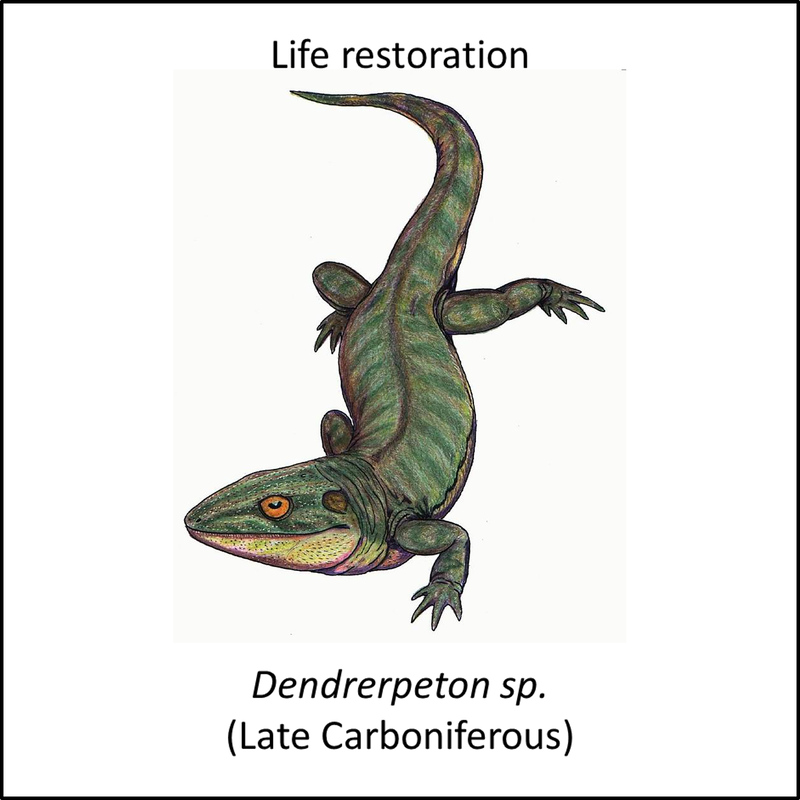

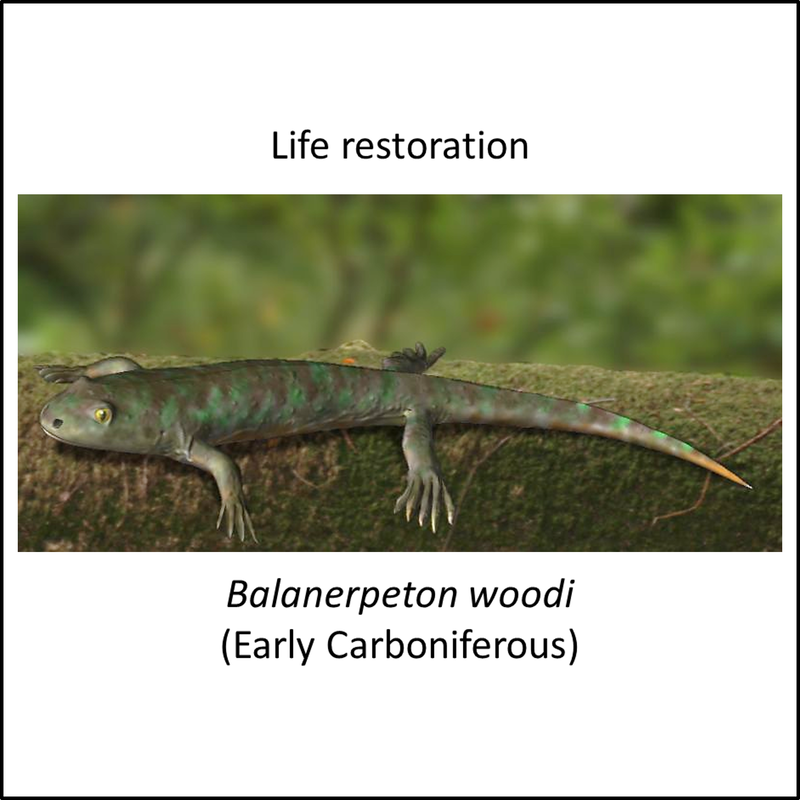

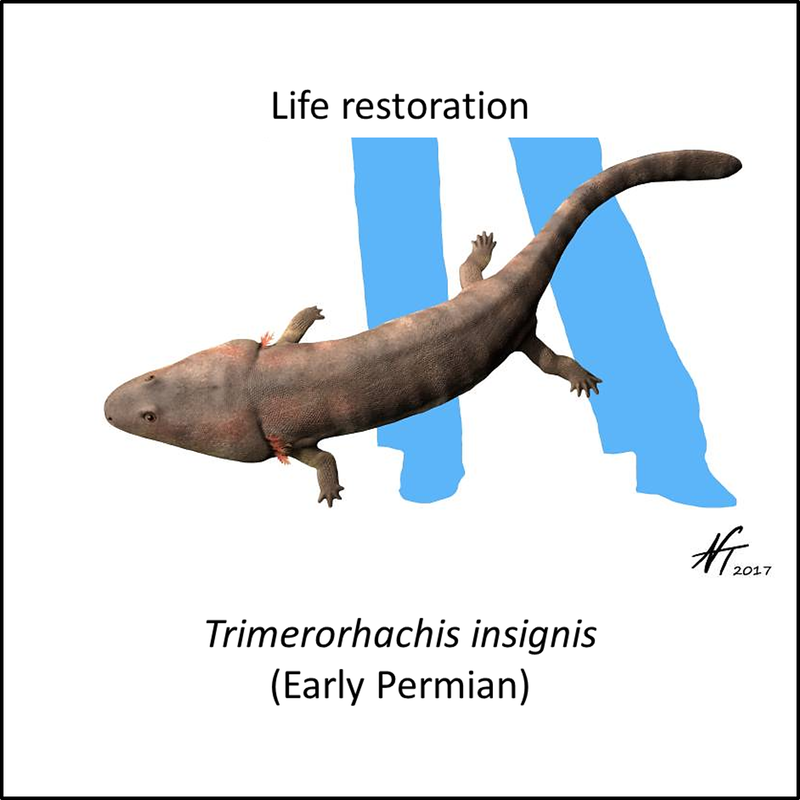

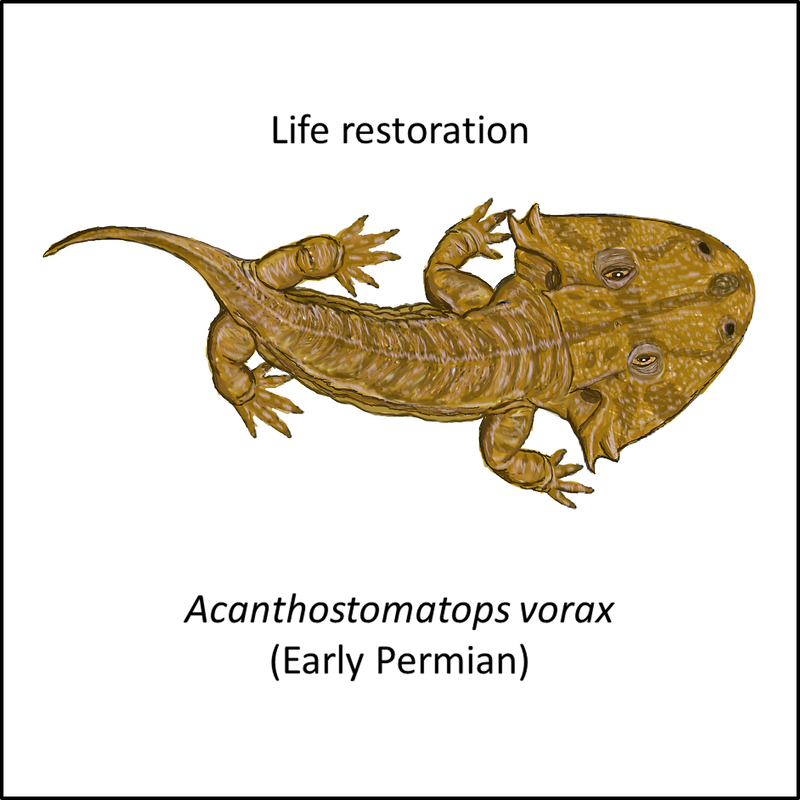

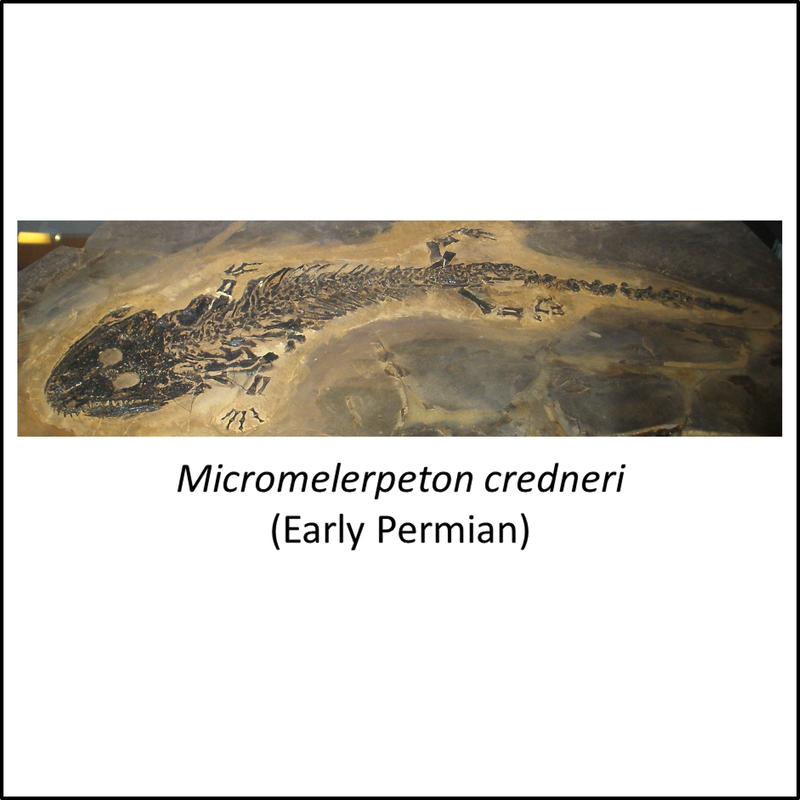

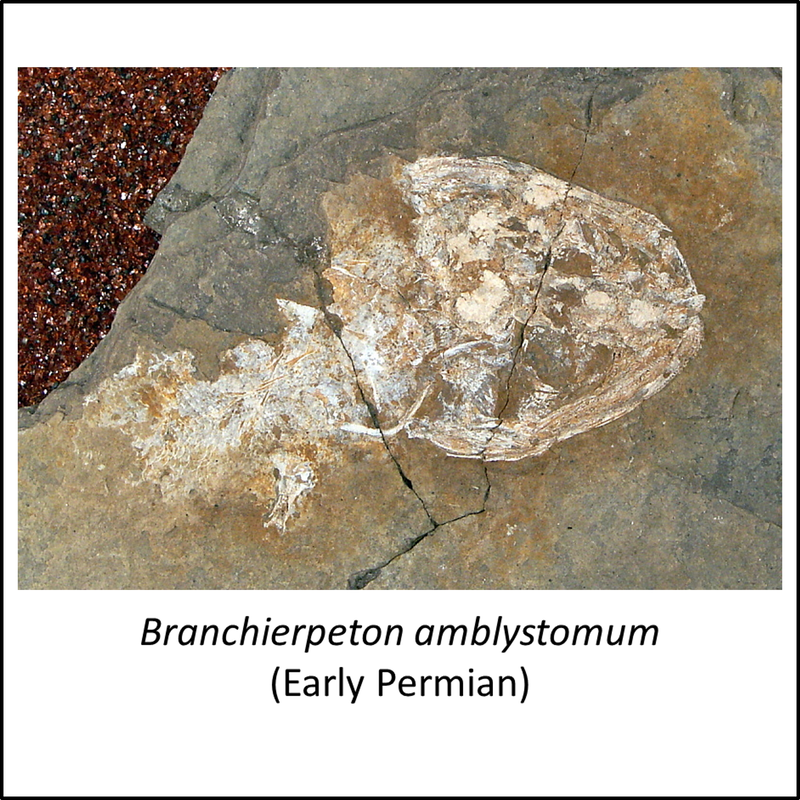

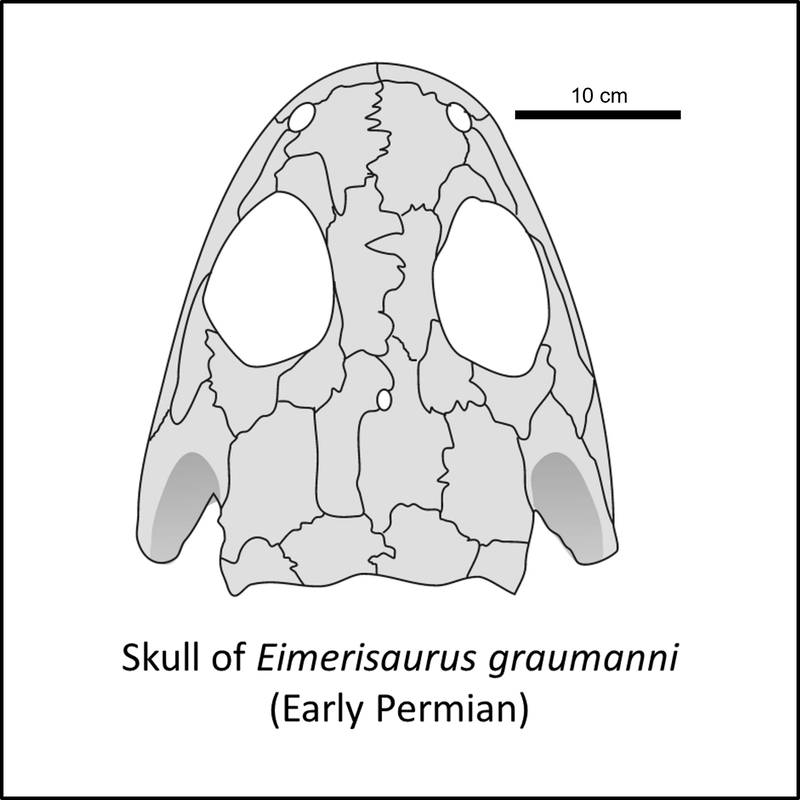

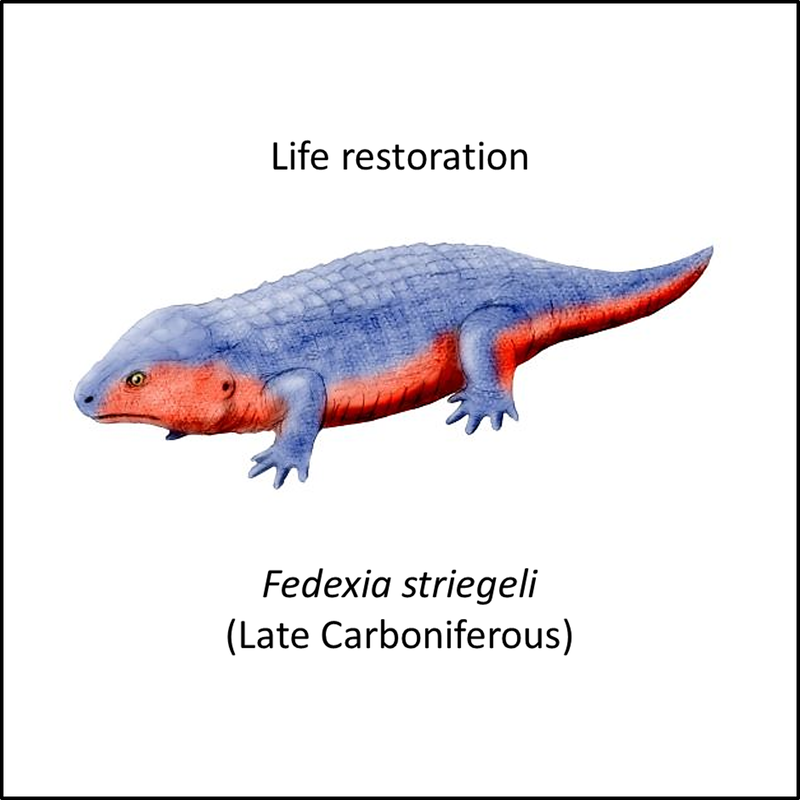

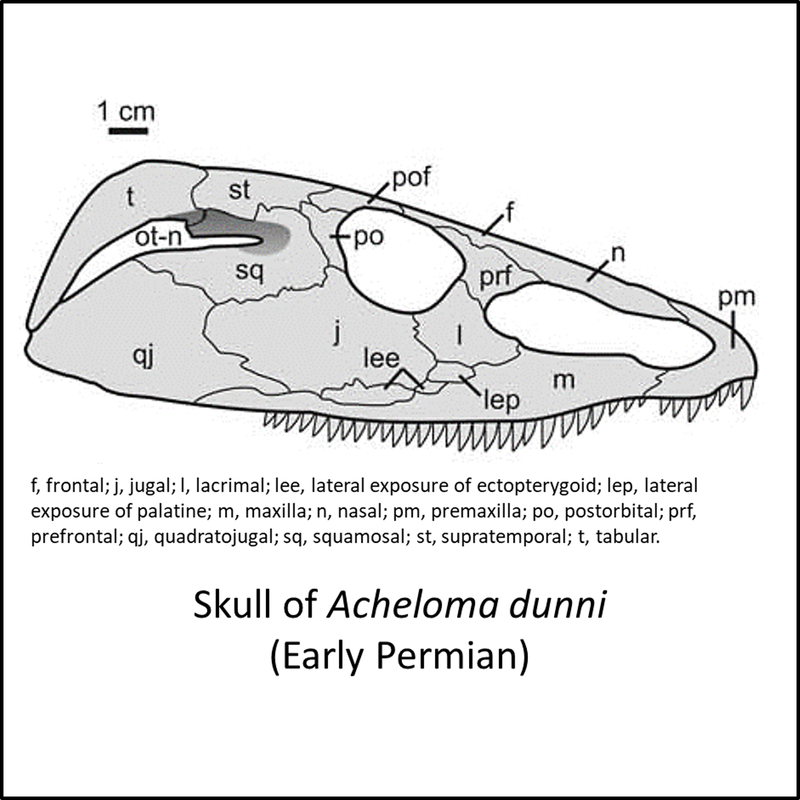

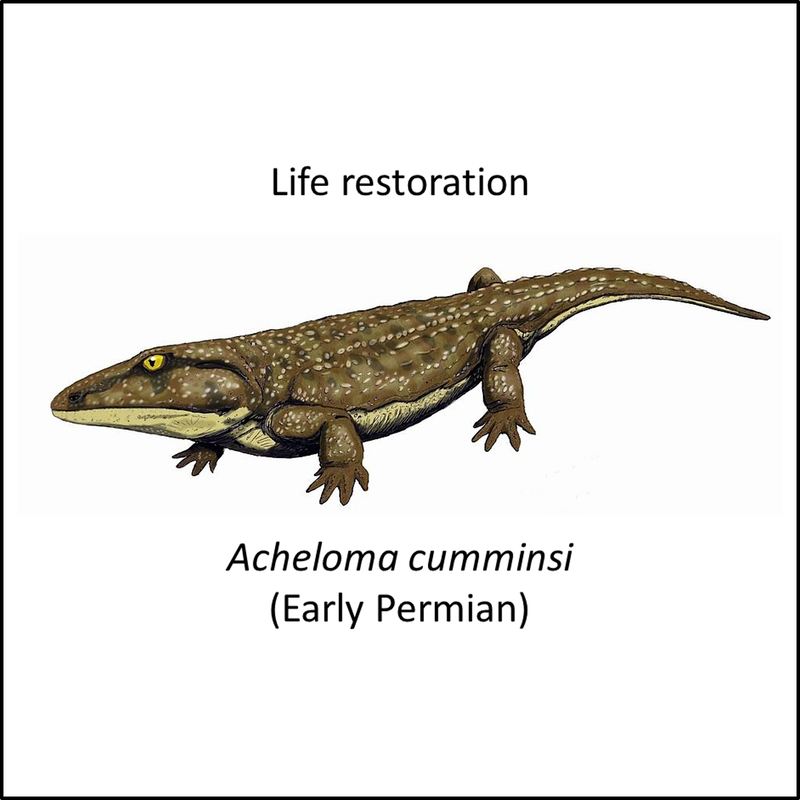

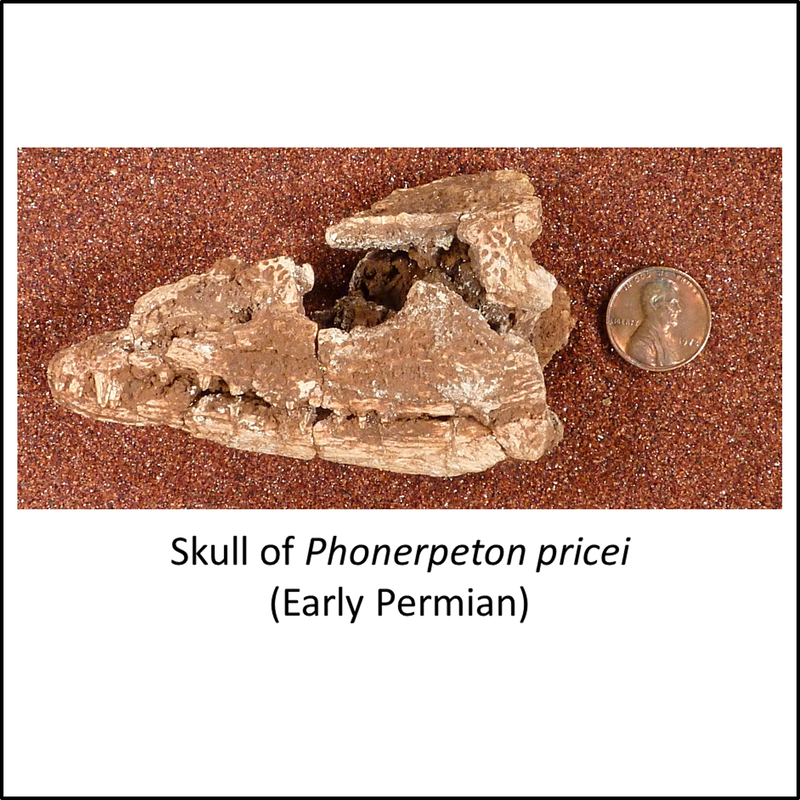

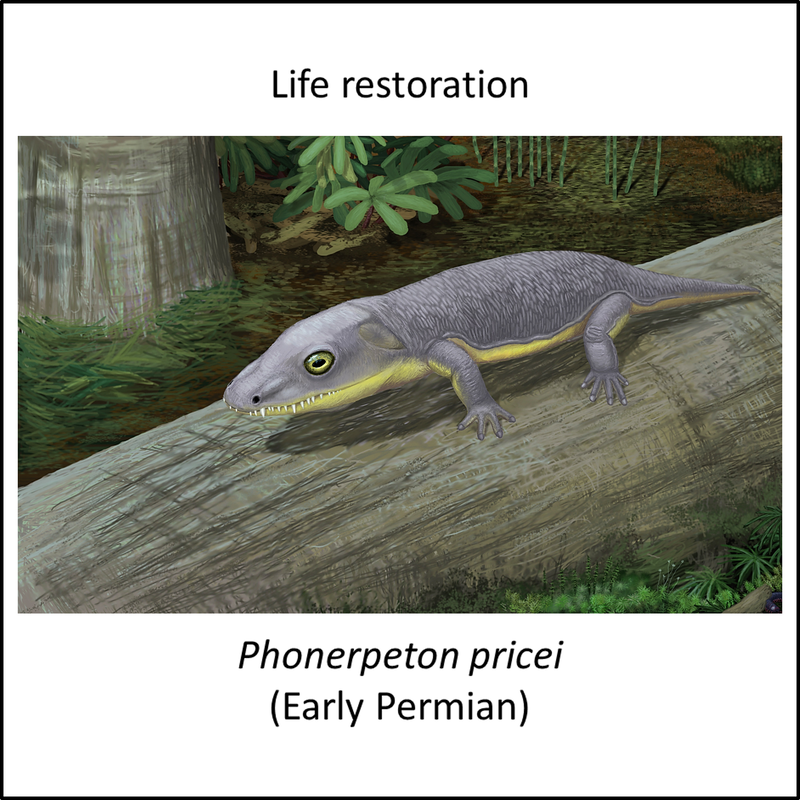

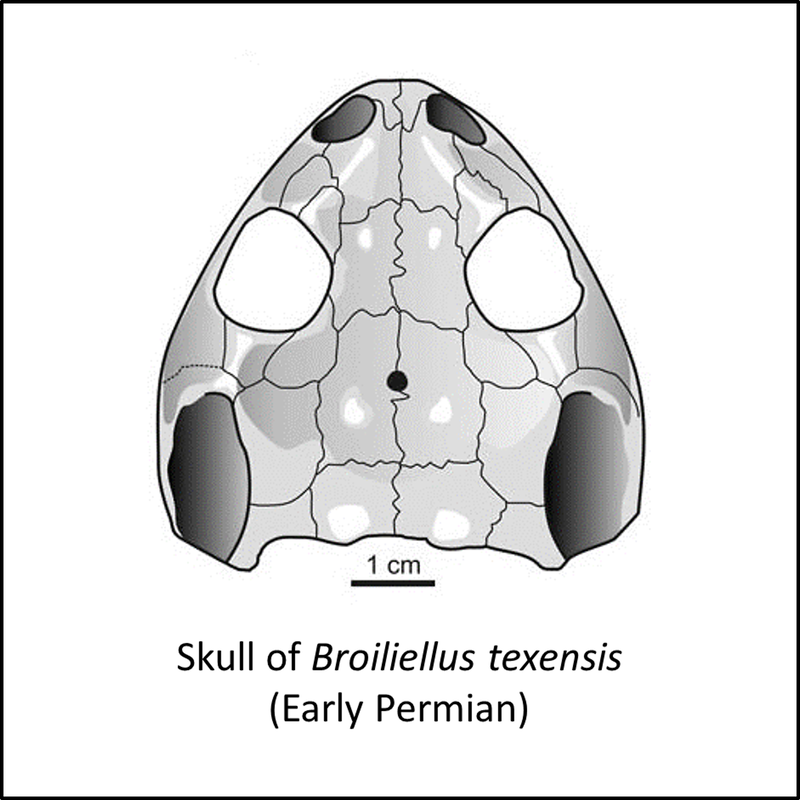

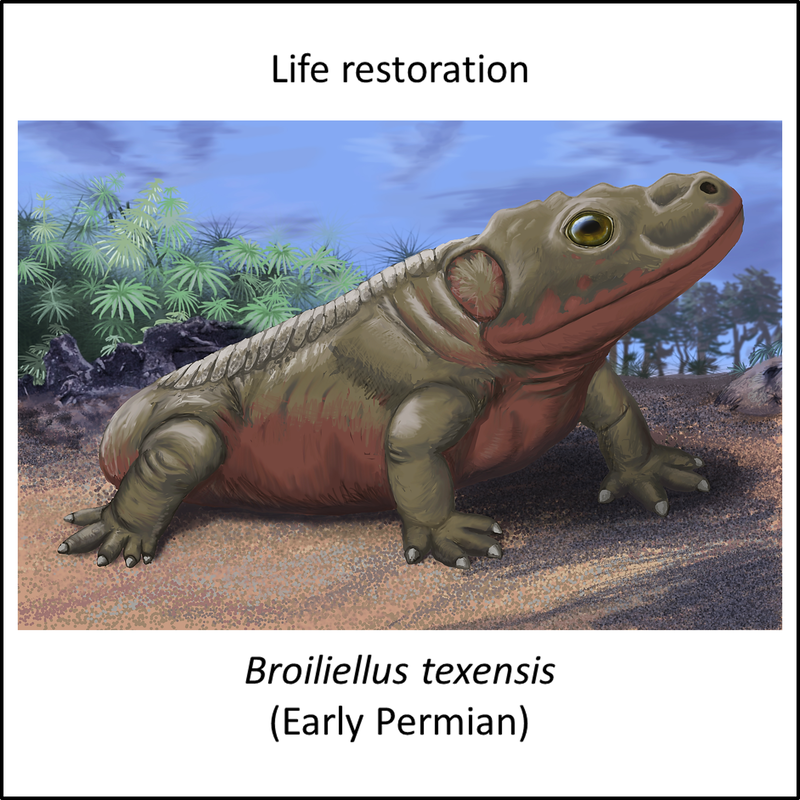

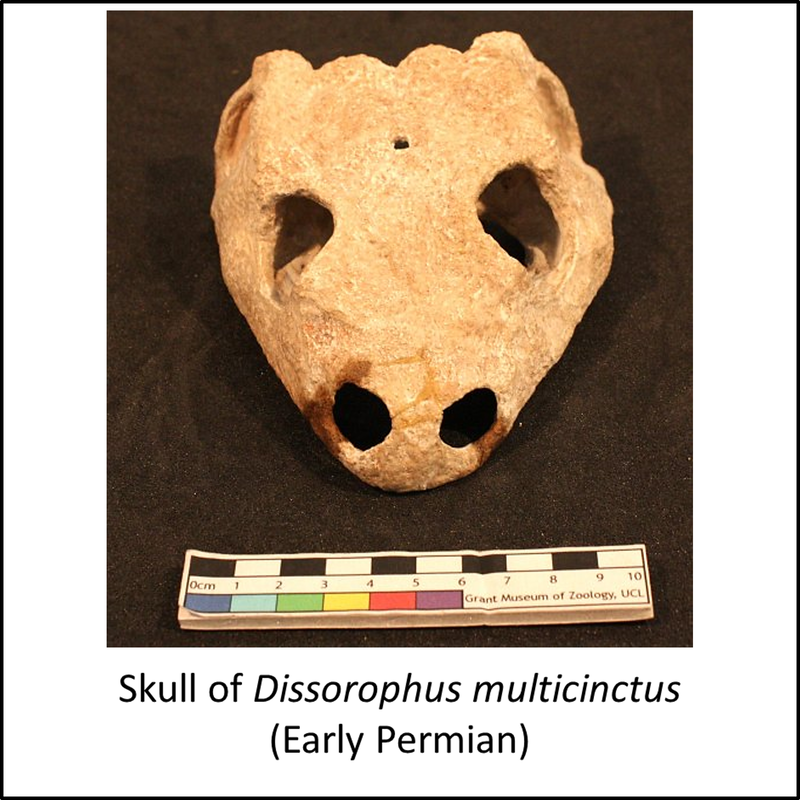

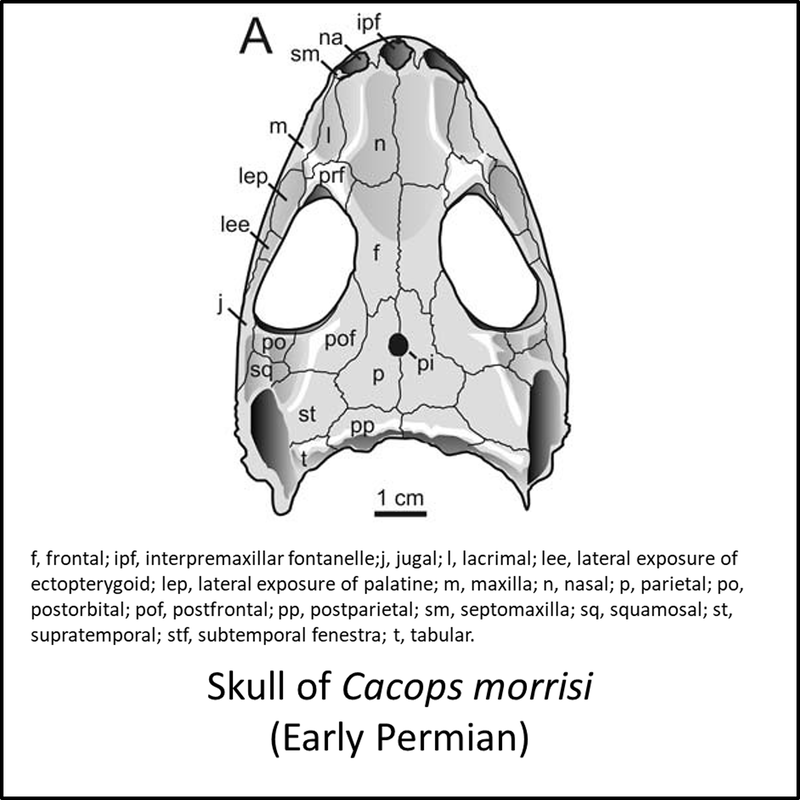

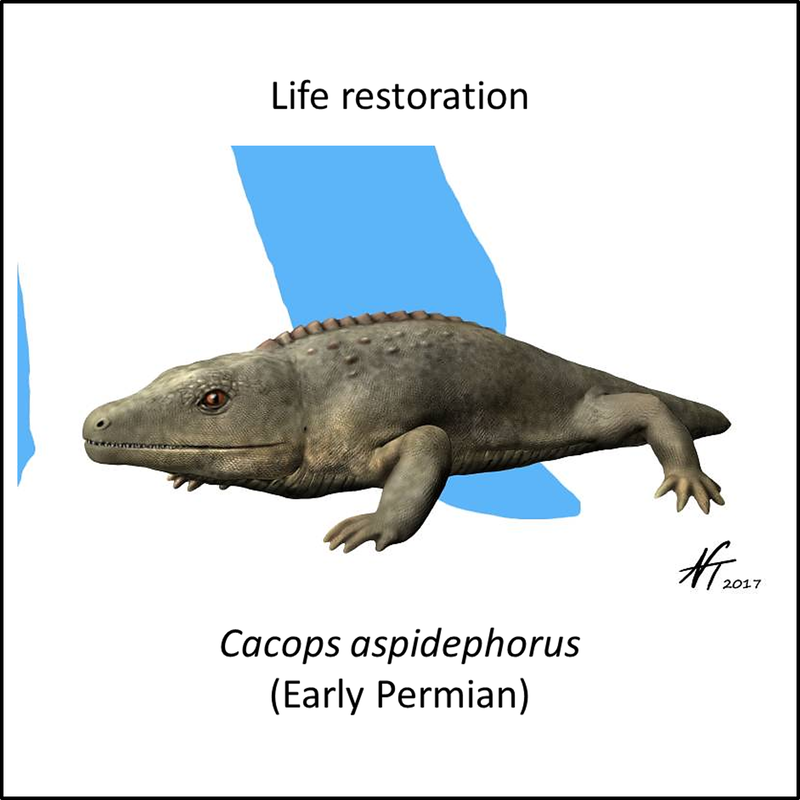

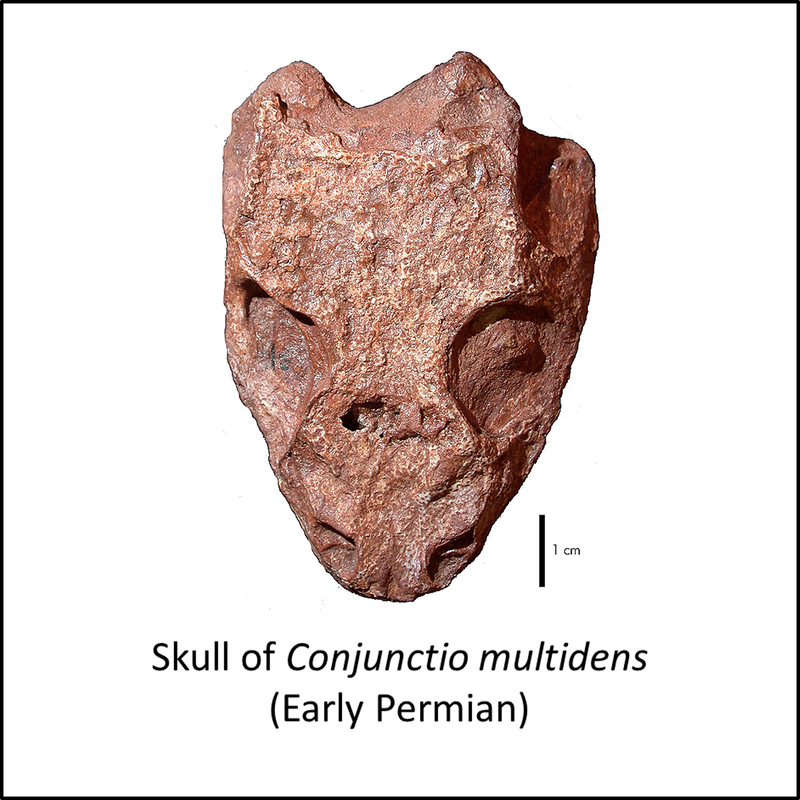

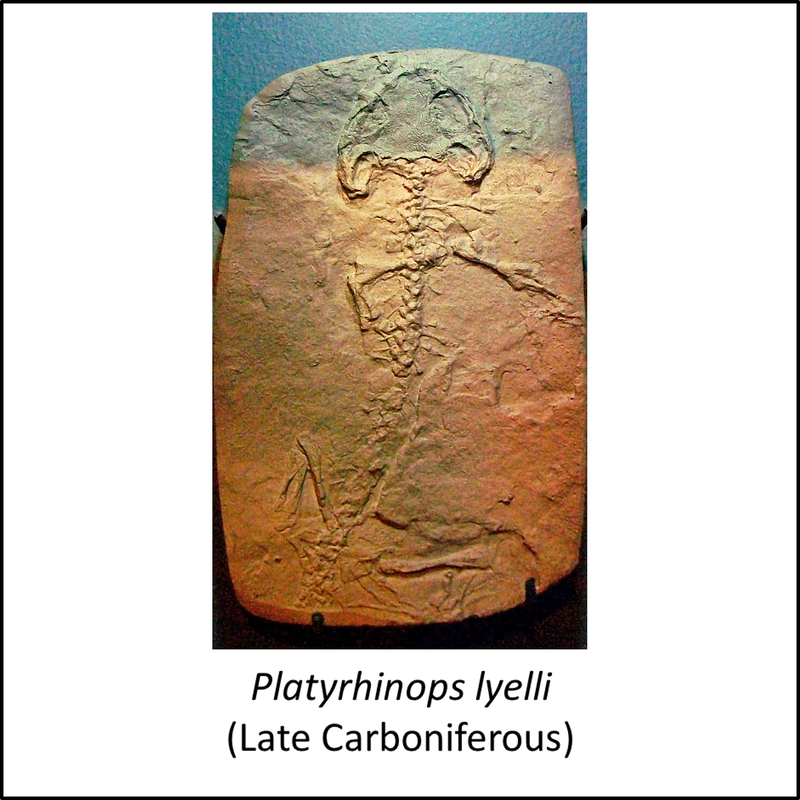

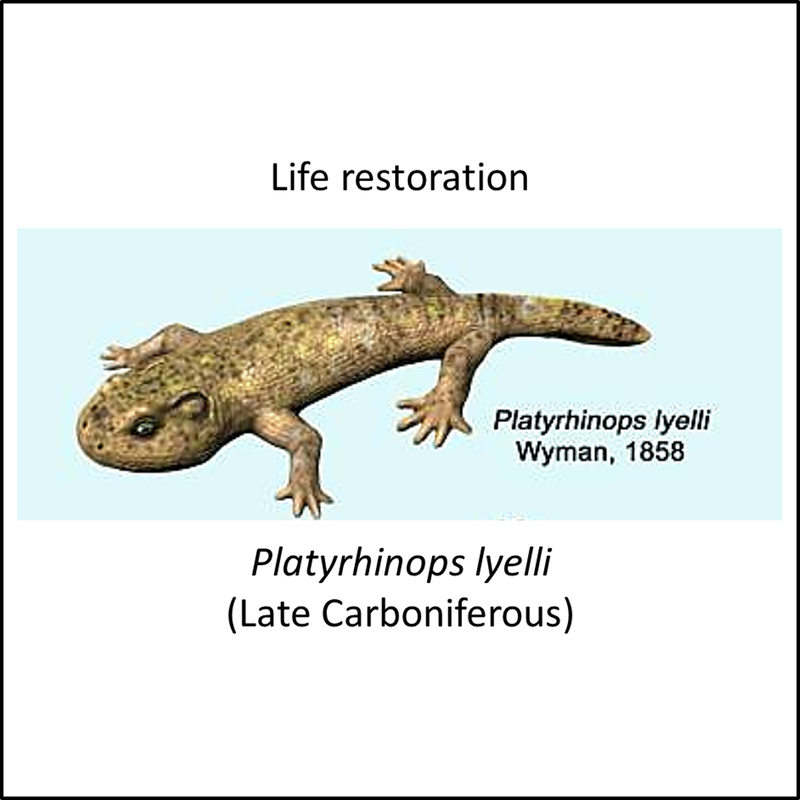

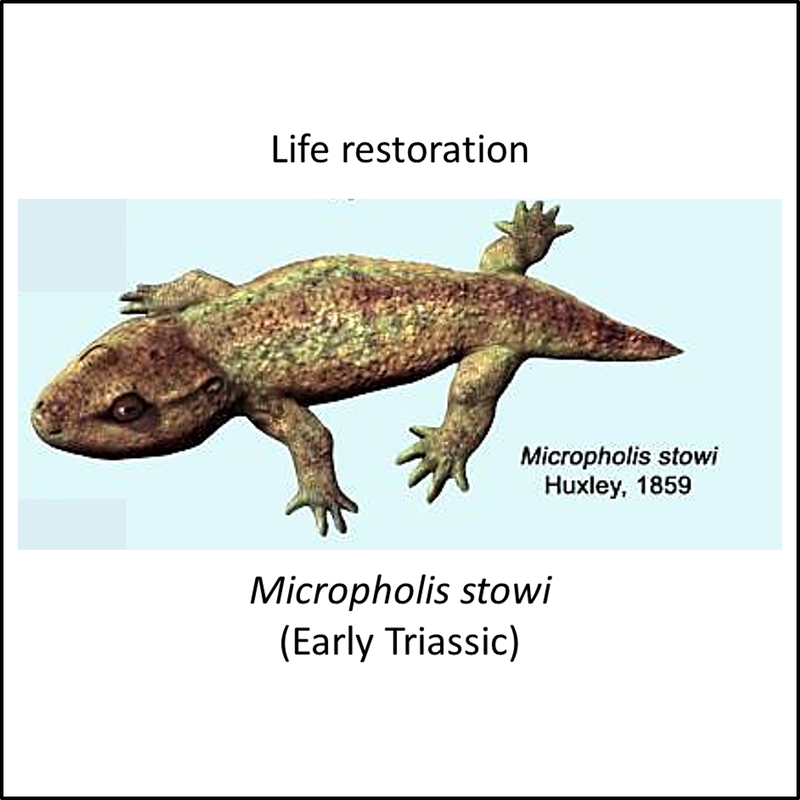

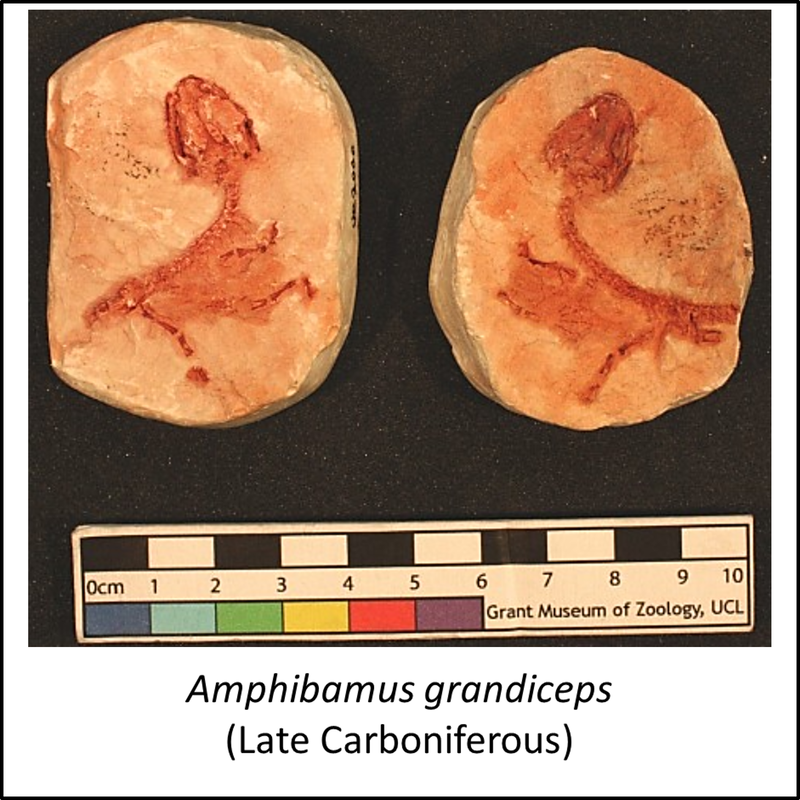

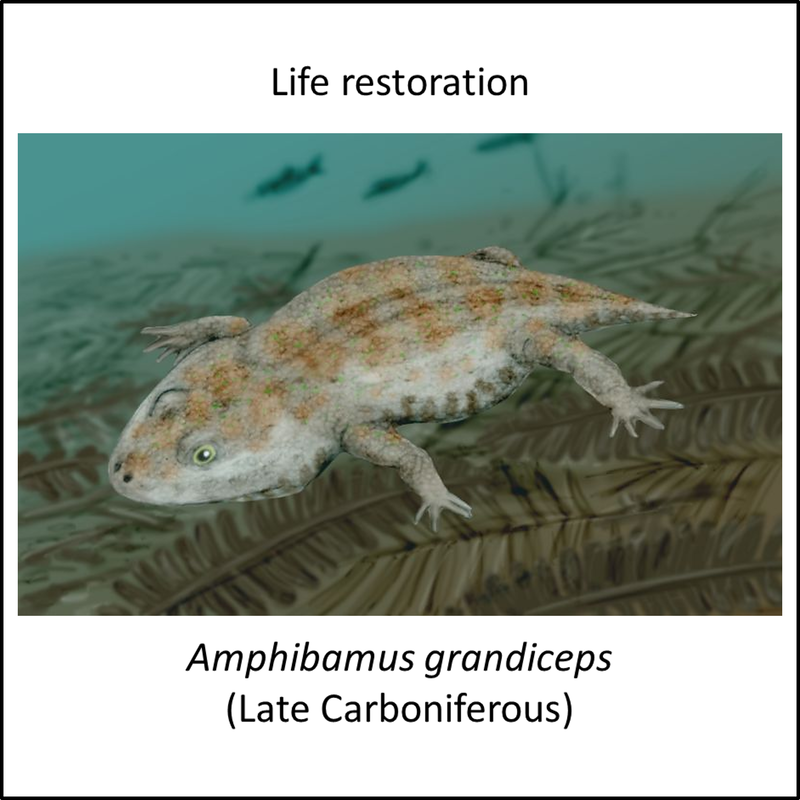

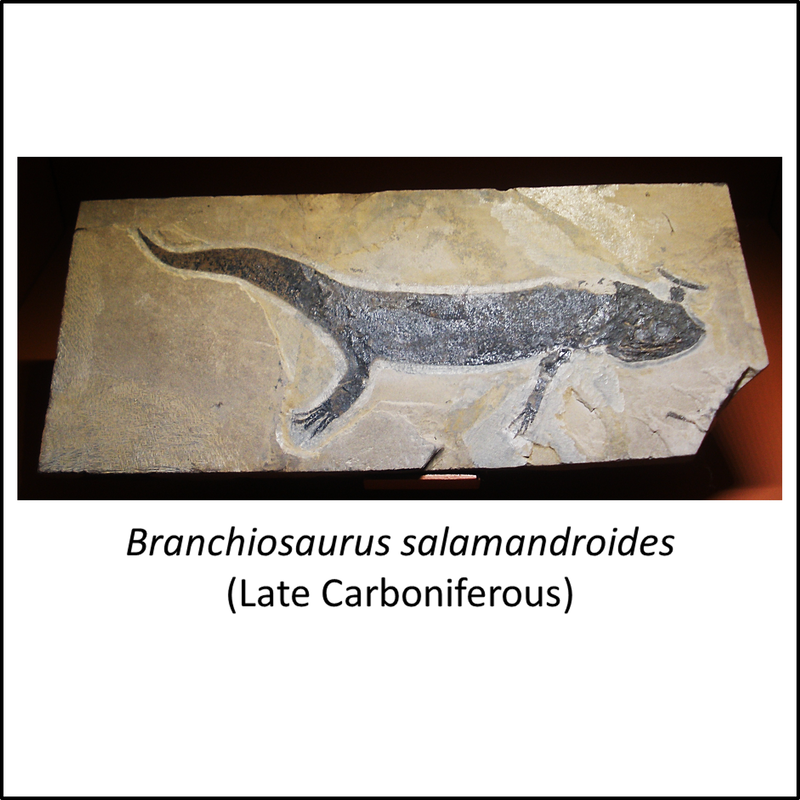

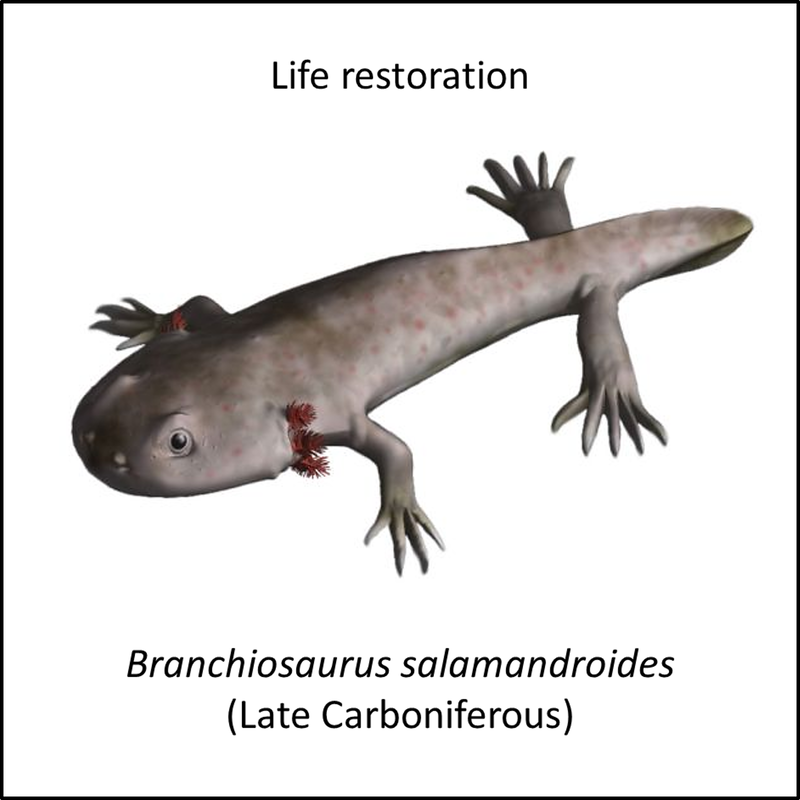

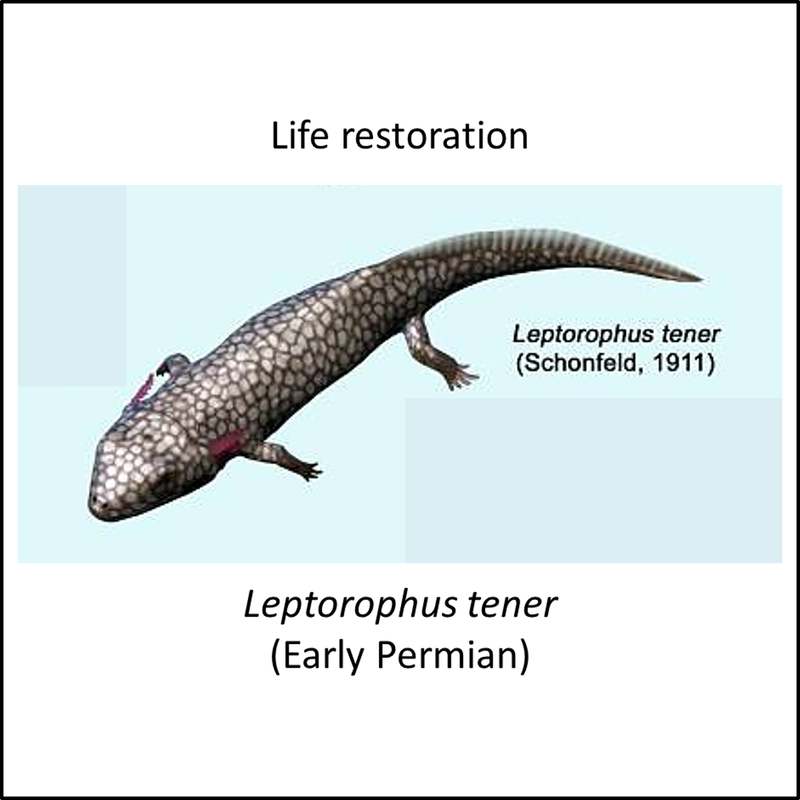

The earliest known representative of the amphibian stem group is Balanerpeton woodi, found in the Early Carboniferous sediments in the East Kirkton Quarry, Bathgate, near Edinburgh, Scotland (Milner and Sequeira, 1993; Schoch, 2013). This species is illustrated, together with other fossil representatives of the stem group, in the following figure (for larger versions, click on images). The fossils are placed in the order in which they appear in the above phylogenetic tree. The following series of images thus illustrates the transition from the most basal forms to species that are closest to the crown group:

The earliest known representative of the amphibian stem group is Balanerpeton woodi, found in the Early Carboniferous sediments in the East Kirkton Quarry, Bathgate, near Edinburgh, Scotland (Milner and Sequeira, 1993; Schoch, 2013). This species is illustrated, together with other fossil representatives of the stem group, in the following figure (for larger versions, click on images). The fossils are placed in the order in which they appear in the above phylogenetic tree. The following series of images thus illustrates the transition from the most basal forms to species that are closest to the crown group:

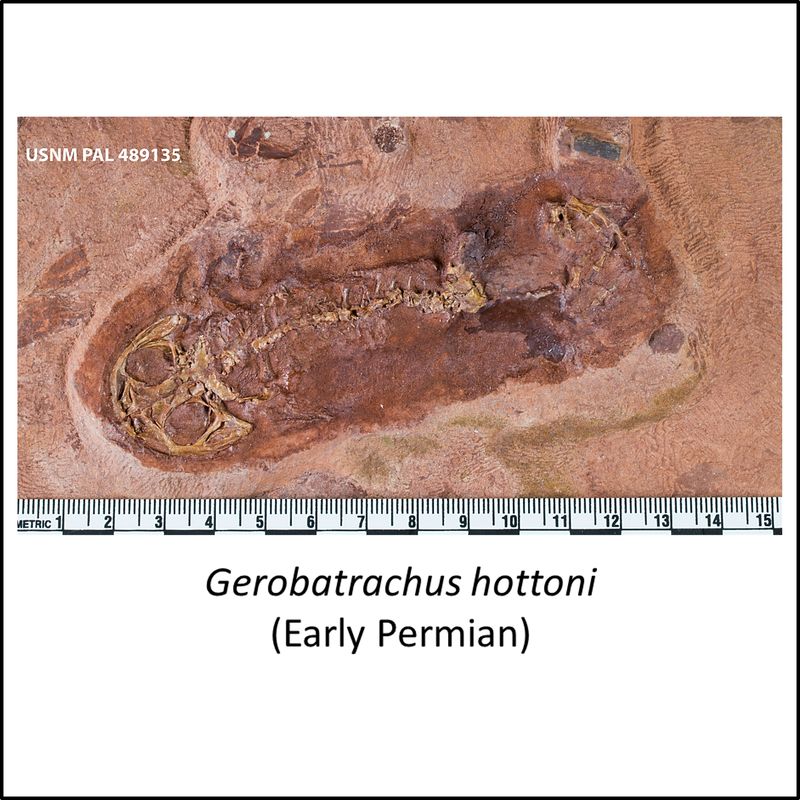

Figure 2. Images of stem-group amphibians

The images shown above do not lend themselves to recognition of the synapomorphies outlined above. To the casual observer there is no obvious consistent change through the series, except for a general shortening of tail length relative to total body length and the fact that some of the species closest to the crown group appear rather frog-like (e.g. Cacops, Amphibamus, Gerobatrachus). However, phylogenetic analysis (e.g. Schoch, 2019) has demonstrated important changes in skull morphology along the amphibian stem line.

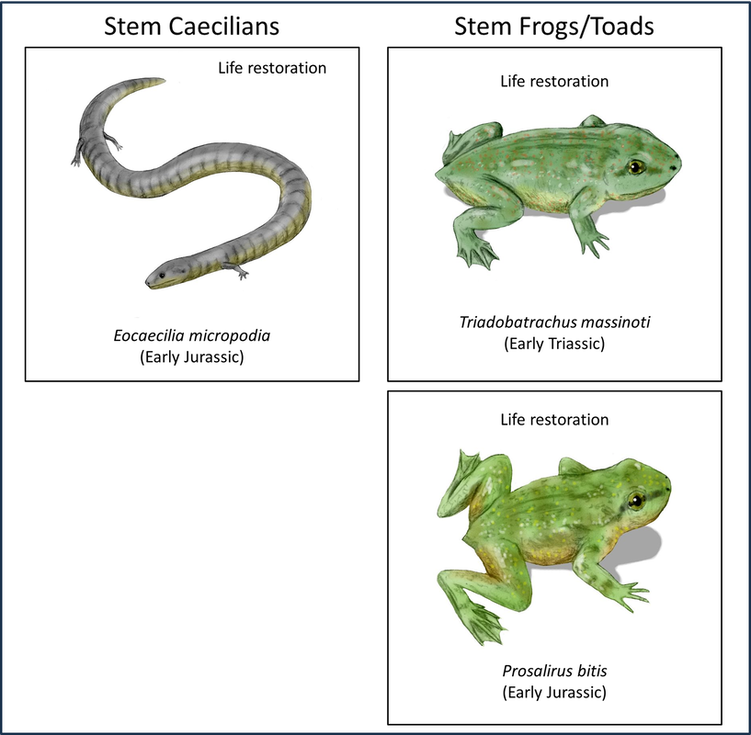

Some idea of the nature of the transition from the stem group to the crown group of the amphibians can be derived from a comparison of the above images with the examples of early crown-Amphibia shown below:

Some idea of the nature of the transition from the stem group to the crown group of the amphibians can be derived from a comparison of the above images with the examples of early crown-Amphibia shown below:

Figure 3. Examples of early crown-Amphibia

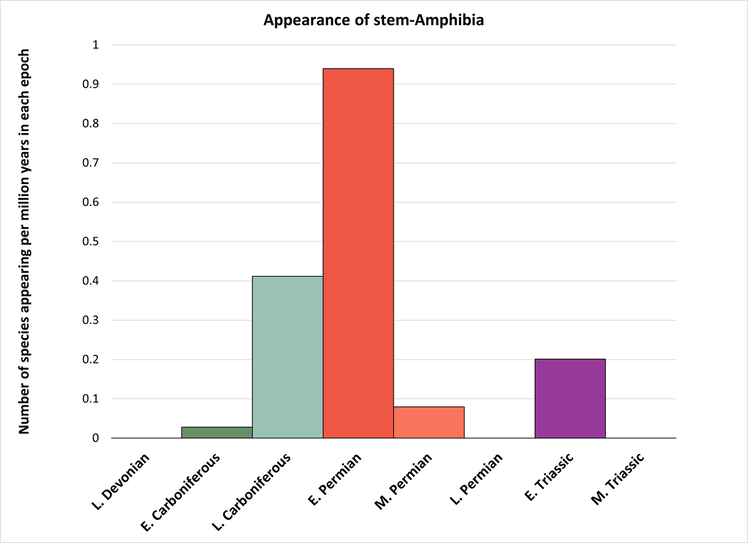

The above time tree (Figure 1) indicates that the amphibian stem group developed from Early Carboniferous to Early Triassic time, representing a stem-to-crown transition of at least 80 million years. However, as shown below, the highest rate of appearance of the stem-group genera represented in Figure 1 occurred during the Early Permian, an epoch that lasted only 27 million years:

Figure 4. Rate of appearance of stem-group amphibians (for only the genera shown in Figure 1)

References

Anderson, J. S. (2001). The phylogenetic trunk: maximal inclusion of taxa with missing data in an analysis of the Lepospondyli (Vertebrata, Tetrapoda). Systematic Biology, 50(2), 170-193.

Atkins, J. B., Reisz, R. R., & Maddin, H. C. (2019). Braincase simplification and the origin of lissamphibians. PloS one, 14(3), e0213694.

Benton, M. J. (2015). Vertebrate Palaeontology - Fourth edition. John Wiley & Sons, 468 pages.

Laurin, M., Reisz, R. R., Sumida, S. S., & Martin, K. L. M. (1997). A new perspective on tetrapod phylogeny. Amniote origins: completing the transition to land, in Sumida S.S., and Martin, K.L., eds., Amniote Origins: New York, Academic Press, p. 9–59.

Marjanović, D., & Laurin, M. (2019). Phylogeny of Paleozoic limbed vertebrates reassessed through revision and expansion of the largest published relevant data matrix, PeerJ, 6, e5565.

Milner, A. R., & Sequeira, S. E. K. (1993). The temnospondyl amphibians from the Viséan of east Kirkton, West Lothian, Scotland. Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 84(3-4), 331-361.

Pardo, J. D., Szostakiwskyj, M., Ahlberg, P. E., & Anderson, J. S. (2017). Hidden morphological diversity among early tetrapods. Nature, 546(7660), 642-645.

Ruta, M., and Coates, M.I. (2007). Dates, nodes, and character conflict: addressing the lissamphian origin problem: Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, v. 5, p. 69–122.

Ruta, M., Krieger, J., Angielczyk, K. D., & Wills, M. A. (2018). The evolution of the tetrapod humerus: Morphometrics, disparity, and evolutionary rates. Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 109(1-2), 351-369.

Schoch, R. R. (2013). The evolution of major temnospondyl clades: an inclusive phylogenetic analysis. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 11(6), 673-705.

Schoch, R. R. (2019). The putative lissamphibian stem-group: phylogeny and evolution of the dissorophoid temnospondyls. Journal of Paleontology, 93(1), p. 137–156. (doi: 10.1017/jpa.2018.67)

Sigurdsen, T., & Green, D. M. (2011). The origin of modern amphibians: a re-evaluation. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 162(2), 457-469.

Atkins, J. B., Reisz, R. R., & Maddin, H. C. (2019). Braincase simplification and the origin of lissamphibians. PloS one, 14(3), e0213694.

Benton, M. J. (2015). Vertebrate Palaeontology - Fourth edition. John Wiley & Sons, 468 pages.

Laurin, M., Reisz, R. R., Sumida, S. S., & Martin, K. L. M. (1997). A new perspective on tetrapod phylogeny. Amniote origins: completing the transition to land, in Sumida S.S., and Martin, K.L., eds., Amniote Origins: New York, Academic Press, p. 9–59.

Marjanović, D., & Laurin, M. (2019). Phylogeny of Paleozoic limbed vertebrates reassessed through revision and expansion of the largest published relevant data matrix, PeerJ, 6, e5565.

Milner, A. R., & Sequeira, S. E. K. (1993). The temnospondyl amphibians from the Viséan of east Kirkton, West Lothian, Scotland. Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 84(3-4), 331-361.

Pardo, J. D., Szostakiwskyj, M., Ahlberg, P. E., & Anderson, J. S. (2017). Hidden morphological diversity among early tetrapods. Nature, 546(7660), 642-645.

Ruta, M., and Coates, M.I. (2007). Dates, nodes, and character conflict: addressing the lissamphian origin problem: Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, v. 5, p. 69–122.

Ruta, M., Krieger, J., Angielczyk, K. D., & Wills, M. A. (2018). The evolution of the tetrapod humerus: Morphometrics, disparity, and evolutionary rates. Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 109(1-2), 351-369.

Schoch, R. R. (2013). The evolution of major temnospondyl clades: an inclusive phylogenetic analysis. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 11(6), 673-705.

Schoch, R. R. (2019). The putative lissamphibian stem-group: phylogeny and evolution of the dissorophoid temnospondyls. Journal of Paleontology, 93(1), p. 137–156. (doi: 10.1017/jpa.2018.67)

Sigurdsen, T., & Green, D. M. (2011). The origin of modern amphibians: a re-evaluation. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 162(2), 457-469.

Image credits – Stem-Amphibia

- Figure 2 (Cochleosaurus bohemicus): FunkMonk, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Cochleosaurus sp., life restoration): ДиБгд at Russian Wikipedia, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (skull of Edops craigi): BatmanelVisigodo, CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Edops craigi, life restoration): Dmitry Bogdanov, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Eryops megacephalus, fossil): Photographed by Bob James (owner of website) at American Museum of Natural History, New York, May 2024.

- Figure 2 (Eryops megacephalus, life restoration): Nobu Tamura under a Creative Commons 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) license

- Figure 2 (skull of Cheliderpeton vranyi): Hectonichus, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Cheliderpeton vranyi, life restoration): Smokeybjb, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Glanochthon lellbachae): Open Access article Schoch, R. R. (2021). Osteology of the Permian temnospondyl amphibian Glanochthon lellbachae and its relationships. Fossil Record, 24(1), 49-64.

- Figure 2 (Australerpeton cosgriffi): Dmitry Bogdanov, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (skull of Archegosaurus decheni): Ghedoghedo, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0CC BY-SA 3.0 Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Archegosaurus decheni, life restoration): Nobu Tamura under Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike (CC BY-SA) license

- Figure 2 (Dendrerpeton acadianum): Gary Todd, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Dendrerpeton sp., life restoration): ДиБгд, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Balanerpeton woodi): Nobu Tamura under a Creative Commons 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) license

- Figure 2 (skull of Trimerorhachis insignis): Photographed by Bob James (owner of website) at American Museum of Natural History, New York, May 2024.

- Figure 2 (Trimerorhachis insignis, life restoration): Nobu Tamura under Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike (CC BY-SA) license

- Figure 2 (Acanthostomatops vorax): Dmitry Bogdanov, CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Micromelerpeton credneri): Ghedoghedo, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Branchierpeton amblystomum): https://www.si.edu/object/branchierpeton-amblystomum-credner:nmnhpaleobiology_3589507, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Eimerisaurus graumanni): Open Access article Schoch, R. R. (2019). The putative lissamphibian stem-group: phylogeny and evolution of the dissorophoid temnospondyls. Journal of Paleontology, 93(1), 137-156.

- Figure 2 (Fedexia striegeli): Nobu Tamura under a Creative Commons 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) license

- Figure 2 (skull of Acheloma dunni): Jonathan Chen, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Acheloma cumminsi, life restoration): ДиБгд, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (skull of Phonerpeton pricei): Smithsonian Institution, public domain

- Figure 2 (Phonerpeton pricei, life restoration): Smokeybjb, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (skull of Broiliellus texensis): Open Access article Schoch, R. R. (2012). Character distribution and phylogeny of the dissorophid temnospondyls. Fossil Record, 15(2), 121-137.

- Figure 2 (Broiliellus texensis, life restoration): Smokeybjb, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0CC BY-SA 3.0 Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Dissorophus multicinctus): University College London Creative Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (skull of Cacops morrisi): Jonathan Chen, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Cacops aspidephorus, life restoration): Nobu Tamura under Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike (CC BY-SA) license

- Figure 2 (Conjunctio multidens): Pat Holroyd, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Eoscopus lockardi): Jeyradan, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Platyrhinops lyelli, fossil): Smokeybjb, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Platyrhinops lyelli, life restoration): Nobu Tamura under Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike (CC BY-SA) license

- Figure 2 (Micropholis stowi): Nobu Tamura under Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike (CC BY-SA) license

- Figure 2 (Amphibamus grandiceps, fossil): University College London, under the Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Share Alike 3.0 License

- Figure 2 (Amphibamus grandiceps, life restoration): Nobu Tamura under a Creative Commons 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) license

- Figure 2 (Branchiosaurus salamandroides, fossil): Ghedoghedo, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Branchiosaurus salamandroides, life restoration): Nobu Tamura under a Creative Commons 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) license

- Figure 2 (Apateon gracilis): Florian Witzmann, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Leptorophus tener): Nobu Tamura under Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike (CC BY-SA) license

- Figure 2 (Gerobatrachus hottoni, fossil): https://www.si.edu/object/gerobatrachus-hottoni-anderson-et-al-2008:nmnhpaleobiology_3577932, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Gerobatrachus hottoni, life restoration): Nobu Tamura under a Creative Commons 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) license

- Figure 3 (Eocaecilia macropodia): Nobu Tamura under a Creative Commons 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) license

- Figure 3 (Triadobatrachus massinoti): Nobu Tamura under a Creative Commons 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) license

- Figure 3 (Prosalirus bitis): Nobu Tamura under a Creative Commons 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) license