The caudates (order , class Amphibia) comprise the salamanders (and newts, which comprise a subfamily, Pleurodelinae, within the salamander family Salamandridae). The Caudata are also known as the Urodela, although some researchers (e.g. Marjanović and Laurin, 2013) confine the term Urodela to the crown-salamanders and use the name Caudata for the total group. There are more than 700 species of caudates, distributed between 10 families.

Note that this website does not include a page on the stem group of the clade to which the salamanders belong (the Batrachia). Although one species, Gerobatrachus hottoni, has been assigned to the stem-Batrachia in some analyses (e.g. Anderson et al, 2008; Atkins et al, 2019), others (e.g. Schoch, 2019) have placed it in the stem-Amphibia (as shown in Figure 1 of the stem-Amphibia page). In view of this uncertainty, we do not consider the batrachian stem group to be sufficiently well documented to warrant further discussion here.

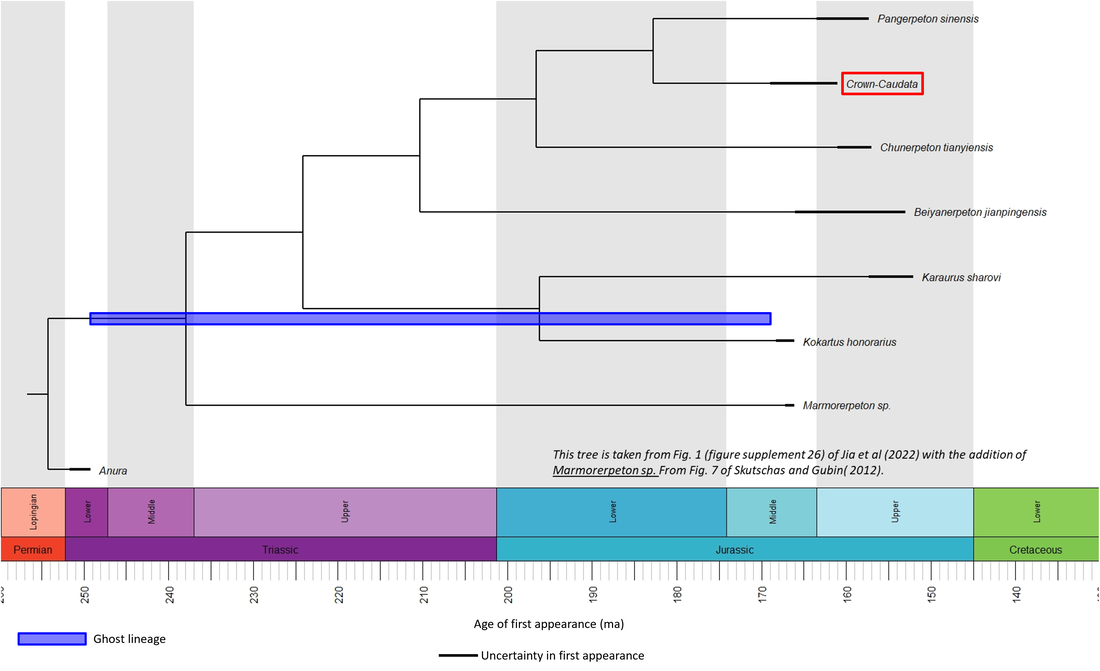

A recent interpretation of the phylogeny of the stem-Urodela, based on a few of the known fossils, is illustrated below:

Note that this website does not include a page on the stem group of the clade to which the salamanders belong (the Batrachia). Although one species, Gerobatrachus hottoni, has been assigned to the stem-Batrachia in some analyses (e.g. Anderson et al, 2008; Atkins et al, 2019), others (e.g. Schoch, 2019) have placed it in the stem-Amphibia (as shown in Figure 1 of the stem-Amphibia page). In view of this uncertainty, we do not consider the batrachian stem group to be sufficiently well documented to warrant further discussion here.

A recent interpretation of the phylogeny of the stem-Urodela, based on a few of the known fossils, is illustrated below:

Figure 1. Time tree of the stem-Urodela

The following fossils can be considered as the oldest known members of the stem-Urodela:

- Kokartus honorarius, described from the “Balabansai Suite” of Middle Jurassic (Bathonian) age at three localities in the Kugart River Basin of Kyrgyzstan (Skutschas and Martin, 2011; Jia et al, 2022).

- Two species of the genus Marmorerpeton, first described from the Middle Jurassic (Late Bathonian) sediments at Kirtlington, Oxfordshire, England (Evans et al, 1988; Skutschas and Gubin, 2012).

Names in red indicate that the fossil is younger than the oldest known crown-group fossil.

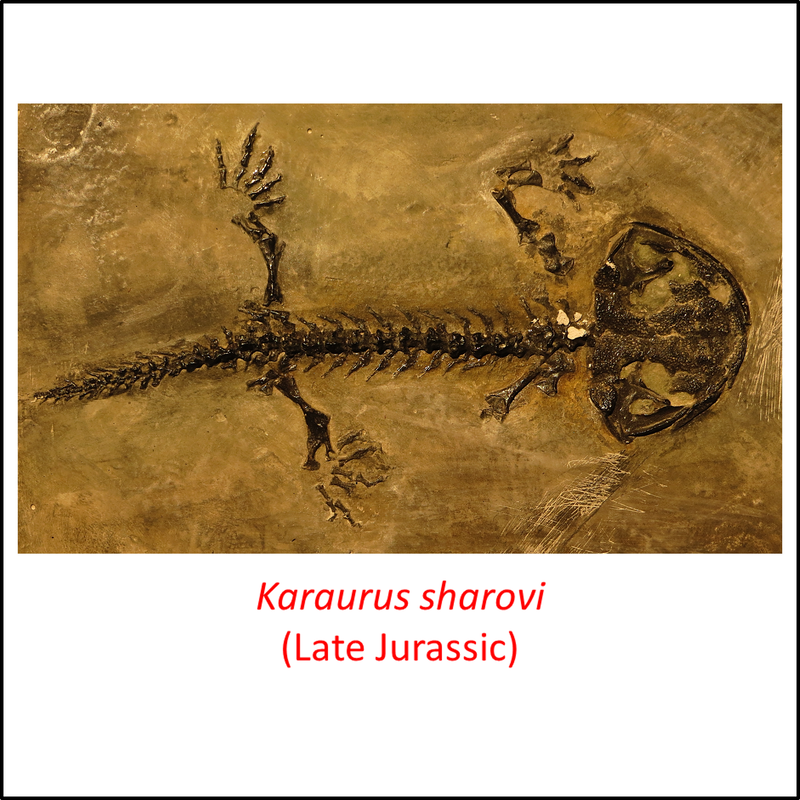

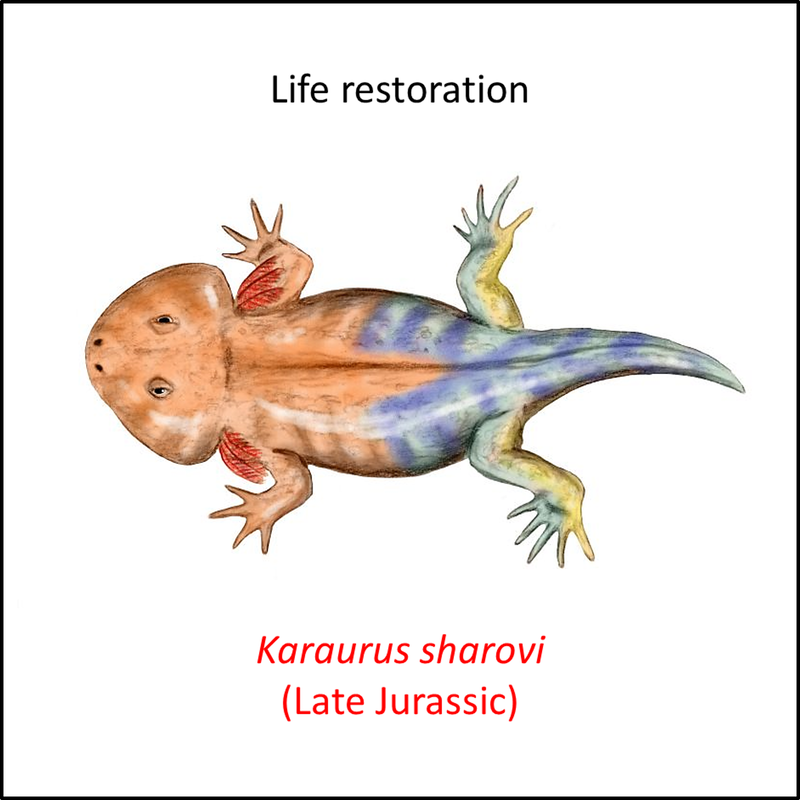

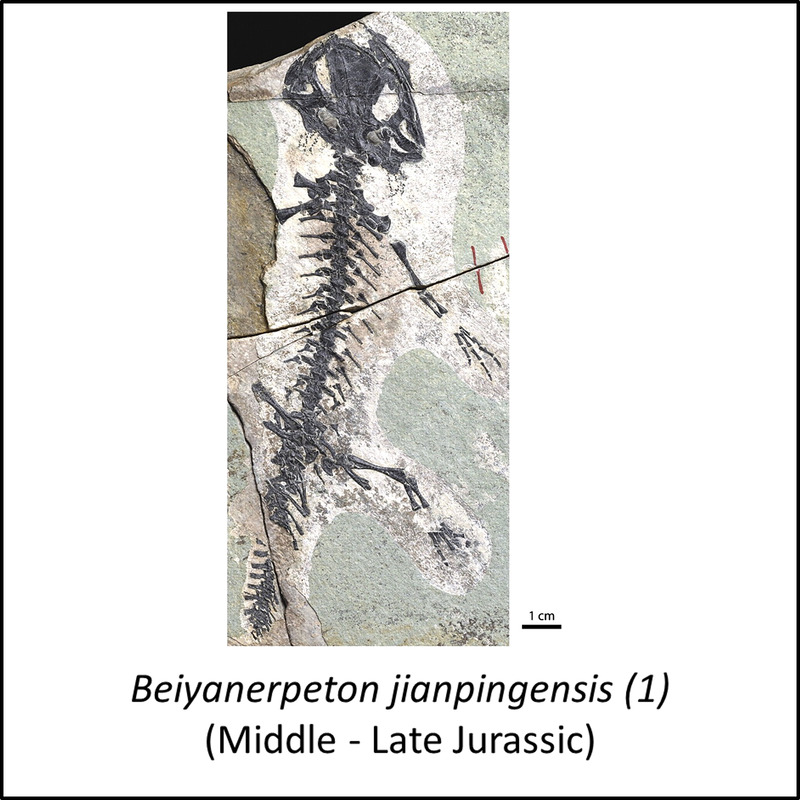

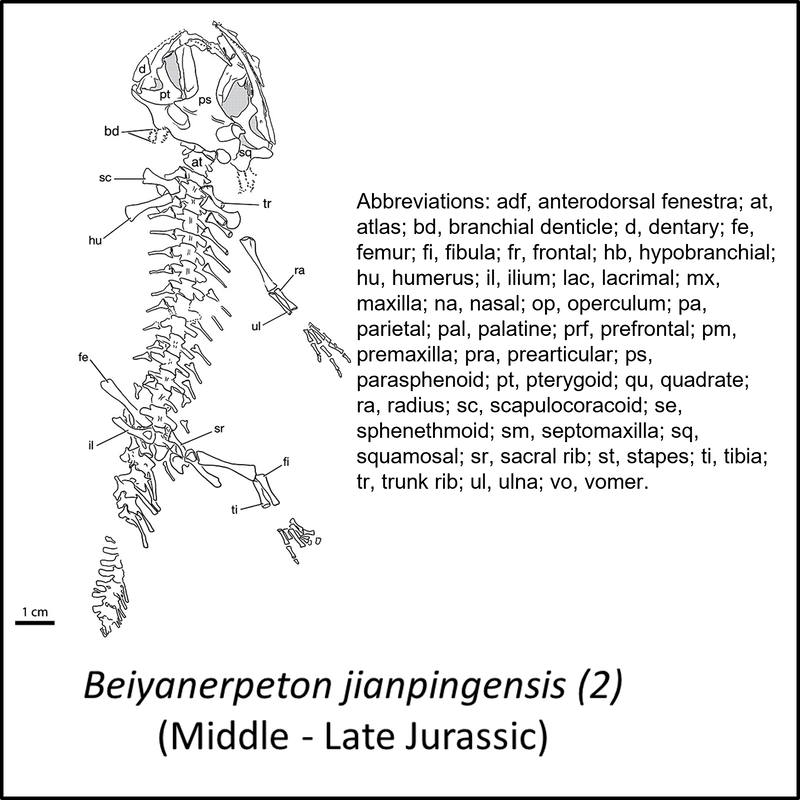

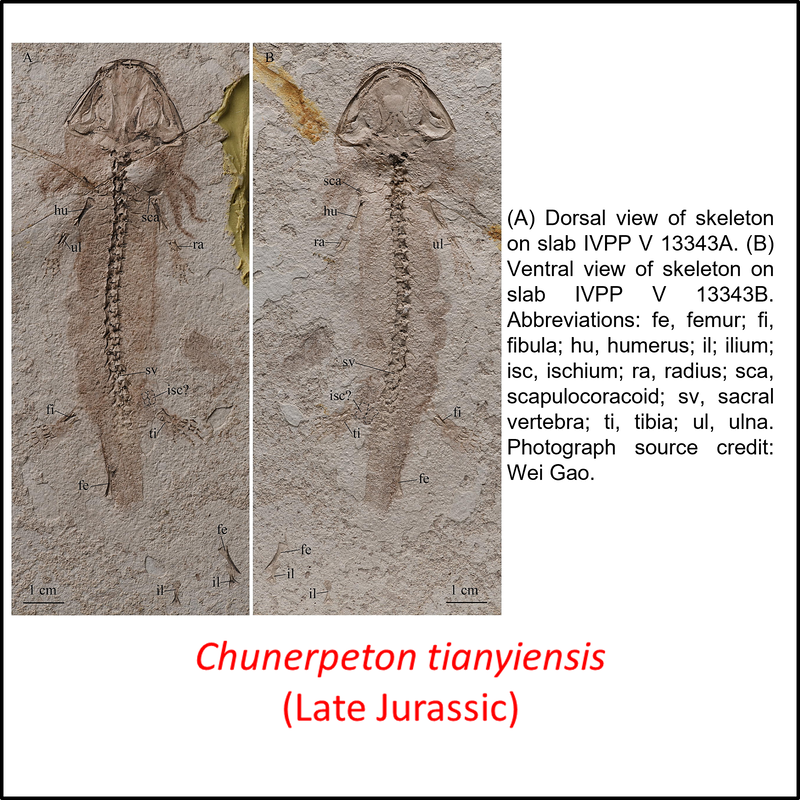

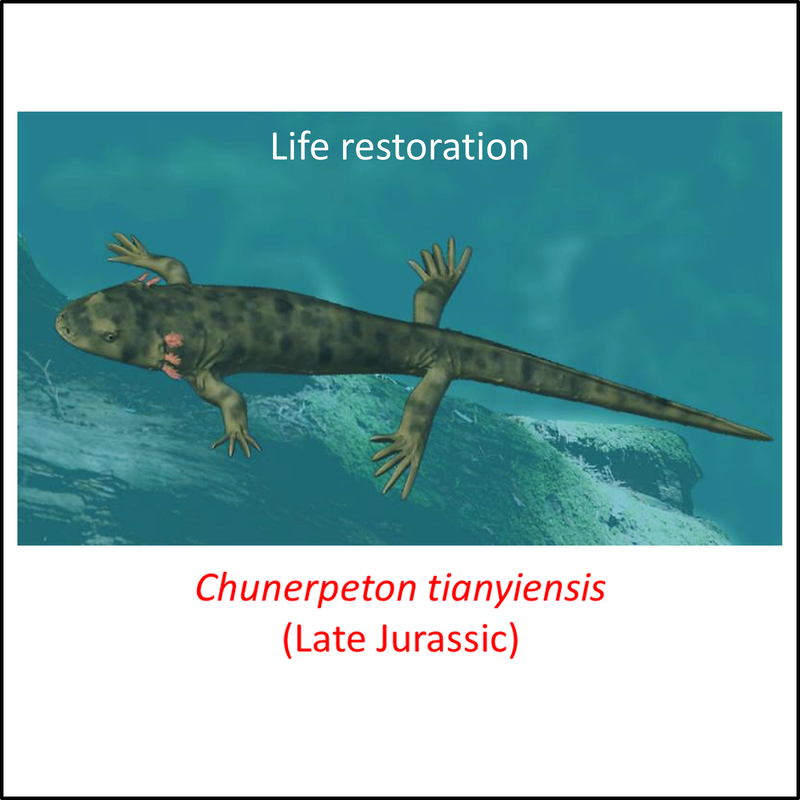

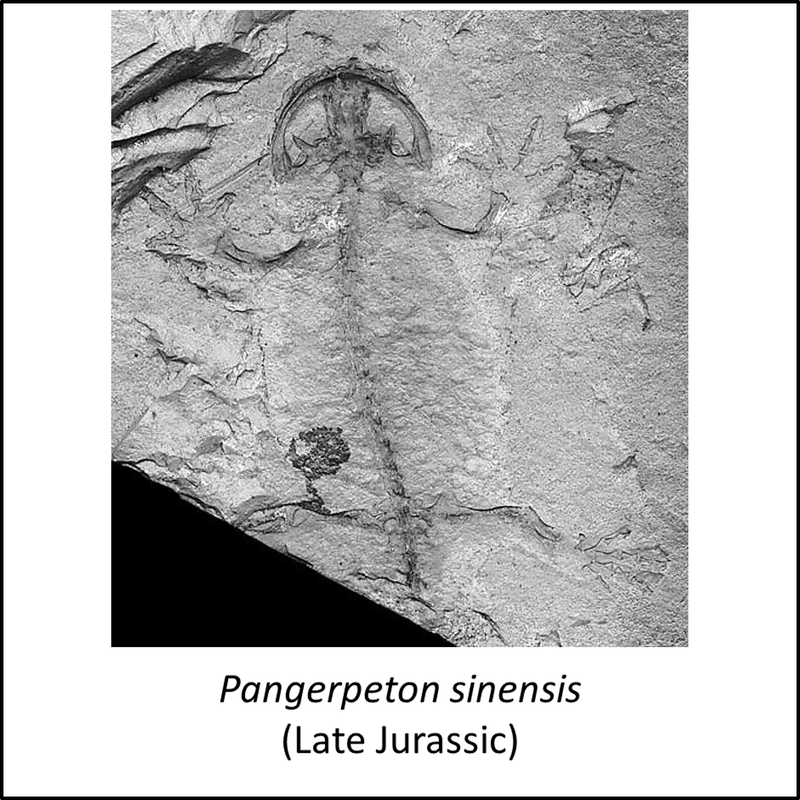

Figure 2. Images of stem-Urodela

Comparison of the above images, placed in order from the most basal forms to species that are closest to the crown group, indicates a trend from a wider to a narrower head, such that one of the more crownward species, Chunerpeton tianyiensis, has at least a superficial resemblance to modern salamanders.

Two fossils that are very close in age represent the oldest known representatives of the salamander crown group:

Two fossils that are very close in age represent the oldest known representatives of the salamander crown group:

- Kiyatriton krasnolutskii, described from the Middle Jurassic (Bathonian) Itat Formation at the Berezovsk Quarry locality in Western Siberia, Russia (Skutschas, 2016). No image is available in the public domain.

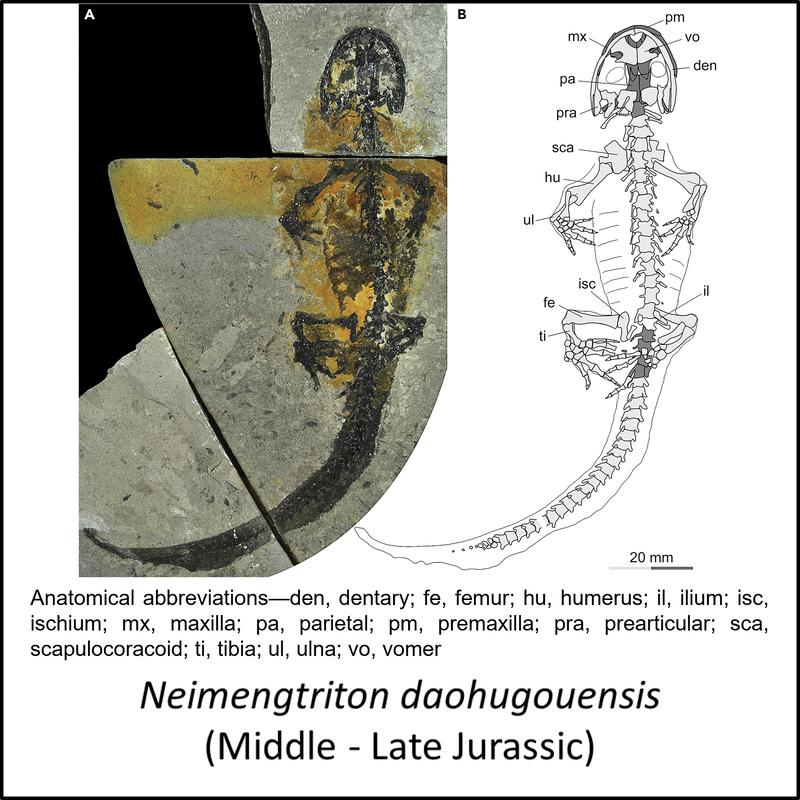

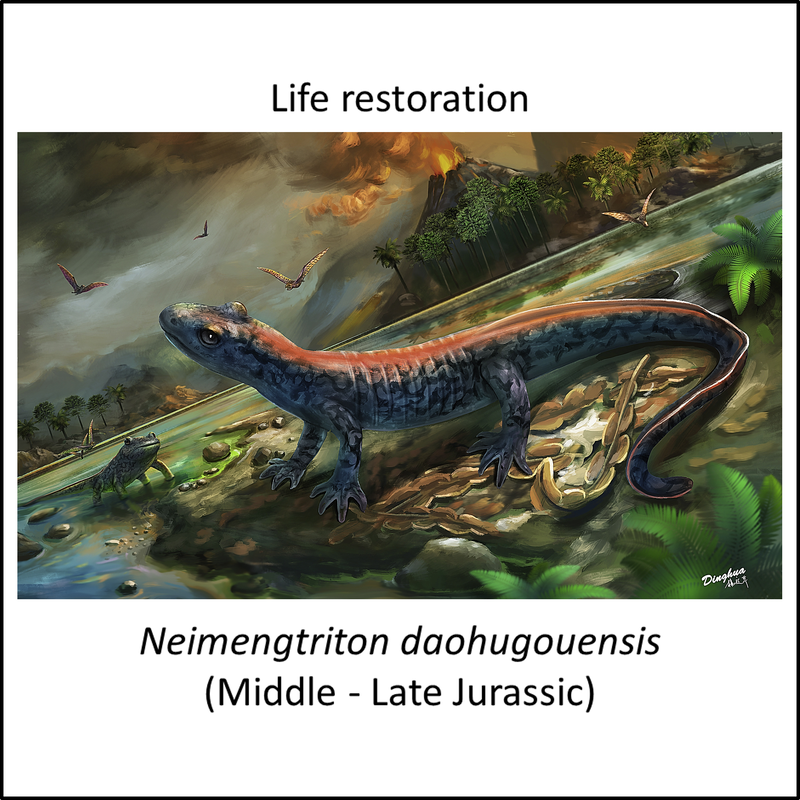

- Neimengtriton daohugouensis, found in the Haifanggou Formation of Middle Jurassic (Bathonian) age at the Daohugou locality, Ningcheng County, Inner Mongolia, China (Jia et al, 2021). A fossil and a life restoration are shown below:

Figure 3. Images of crown-group salamander Neimengtriton daohugouensis

As illustrated above in Figure 1, there is virtually no difference in age between the fossils of the salamander stem group and the oldest crown-group fossil. This contemporaneity corresponds to the big difference in age (around 81 million years) between the salamander stem group and the oldest fossils of the stem-Anura (the frogs and toads). This time gap is represented by the ghost lineage shown in blue in Figure 1. Thus the stem-to-crown transition of the salamanders must also have lasted around 81 million years, from Early Triassic to Middle Jurassic times.

References

Evans, S. E., Milner, A. R., & Mussett, F. (1988). The earliest known salamanders (Amphibia, Caudata): a record from the Middle Jurassic of England. Geobios, 21(5), 539-552.

Jia, J., Li, G., & Gao, K. Q. (2022). Palatal morphology predicts the paleobiology of early salamanders. Elife, 11, e76864.

Marjanović, D., & Laurin, M. (2013). The origin (s) of extant amphibians: a review with emphasis on the “lepospondyl hypothesis”. Geodiversitas, 35(1), 207-272.

Rong, Y. F., Vasilyan, D., Dong, L. P., & Wang, Y. (2021). Revision of Chunerpeton tianyiense (Lissamphibia, Caudata): Is it a cryptobranchid salamander?. Palaeoworld, 30(4), 708-723.

Skutschas, P. P. (2016). A new crown-group salamander from the Middle Jurassic of Western Siberia, Russia. Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments, 96(1), 41-48.

Skutschas, P. P., & Gubin, Y. M. (2012). A new salamander from the late Paleocene—early Eocene of Ukraine. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 57(1), 135-148.

Skutschas, P., & Martin, T. (2011). Cranial anatomy of the stem salamander Kokartus honorarius (Amphibia: Caudata) from the Middle Jurassic of Kyrgyzstan. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 161(4), 816-838.

Jia, J., Li, G., & Gao, K. Q. (2022). Palatal morphology predicts the paleobiology of early salamanders. Elife, 11, e76864.

Marjanović, D., & Laurin, M. (2013). The origin (s) of extant amphibians: a review with emphasis on the “lepospondyl hypothesis”. Geodiversitas, 35(1), 207-272.

Rong, Y. F., Vasilyan, D., Dong, L. P., & Wang, Y. (2021). Revision of Chunerpeton tianyiense (Lissamphibia, Caudata): Is it a cryptobranchid salamander?. Palaeoworld, 30(4), 708-723.

Skutschas, P. P. (2016). A new crown-group salamander from the Middle Jurassic of Western Siberia, Russia. Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments, 96(1), 41-48.

Skutschas, P. P., & Gubin, Y. M. (2012). A new salamander from the late Paleocene—early Eocene of Ukraine. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 57(1), 135-148.

Skutschas, P., & Martin, T. (2011). Cranial anatomy of the stem salamander Kokartus honorarius (Amphibia: Caudata) from the Middle Jurassic of Kyrgyzstan. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 161(4), 816-838.

Image credits – Stem-Urodela

- Header (A spotted salamander (Ambystoma maculatum) in Searsmont, Maine - September 30, 2014): Fyn Kynd Photography from Searsmont, Maine, United States, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Karaurus sharovi, fossil): Ghedoghedo, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2 (Karaurus sharovi, life restoration): Nobu Tamura under a Creative Commons 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) license

- Figure 2 (Beiyanerpeton jianpingensis, 1 and 2): Open Access article Gao, K. Q., & Shubin, N. H. (2012). Late jurassic salamandroid from western liaoning, China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(15), 5767-5772.

- Figure 2 (Chunerpeton tianyiensis, fossil): Open Access article Rong, Y. F., Vasilyan, D., Dong, L. P., & Wang, Y. (2021). Revision of Chunerpeton tianyiense (Lissamphibia, Caudata): Is it a cryptobranchid salamander?. Palaeoworld, 30(4), 708-723.

- Figure 2 (Chunerpeton tianyiensis, life restoration): Nobu Tamura under a Creative Commons 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) license

- Figure 2 (Pangerpeton sinensis): Wang, Y., Evans, S. E., CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 3 (Neimengtriton daohugouensis, fossil): Open Access article Jia, J., Anderson, J. S., & Gao, K. Q. (2021). Middle Jurassic stem hynobiids from China shed light on the evolution of basal salamanders. iScience, 24(7), 102744.

- Figure 3 (Neimengtriton daohugouensis, life restoration): Open Access article Jia, J., Anderson, J. S., & Gao, K. Q. (2021). Middle Jurassic stem hynobiids from China shed light on the evolution of basal salamanders. iScience, 24(7), 102744.